A tribute to esteemed physiologist Professor Ikeda-Wolstencroft from grandson, John Nicholson, and family friend and former colleague Dr Jon Robbins

The Unlocking Futures Fund has been started in memory of Professor Hisako Ikeda-Wolstencroft, a valued member of The Society and a world leader in the field of vision research. In her memory, Professor Ikeda-Wolstencroft’s family made the founding donation to The Society’s new Unlocking Futures Fund with the aim of unlocking the potential of a future leader of physiology.

Dr Jon Robbins, King’s College London, UK is a family friend and former colleague, who shared life in the lab with Professor Ikeda-Wolstencroft. In Dr Jon Robbins account below he notes Professor Ikeda-Wolstencroft as a role model for both work and family life.

Hisako left Japan in 1955/56 with an MA and a young daughter, Utako. She was first employed at the Institute of Psychiatry, London as a Research Assistant where she achieved a PhD by 1960. She obtained a fellowship at the Institute of Ophthalmology, London and was promoted to lecturer of Ophthalmology in 1966. Then moving to the Royal College of Surgeons London as a Senior lecturer in Ophthalmology.

Her final move was to St Thomas’s Hospital Medical School as a Senior Lecturer in Physiology. She was head of the Vision Research Unit at the Rayne Institute at St Thomas’s Hospital by 1974. In 1982 Hisako was made Professor of Visual Physiology which at the time would mean she was one of the very few non white female professors in the country. More recent data from a colleague in the Welcome Trust estimated that in 2017 there were only 54 non white female professors in the UK.

Hisako’s scientific publications range from the effects of ethanol on the function of the eye (1963) through to the effects of Parkinson’s Disease on retinal function (1994) and much between. She published over 110 papers in her career, she has a H-index over 28, total citations of 2380 and it still being cited at around 25 a year (Scopus, Nov 2022). Hisako’s work has let to real world impacts, from advising on the use of sodium streetlights, the treatment of amblyopia and squint, the early identification of retinal dysfunction in Parkinson’s patients and developing a novel animal model for multiple sclerosis. Her work was “bench to bedside” before the term was coined. Simultaneously running a vision electrodiagnostic clinics for private and NHS patients and basic electrophysical research of the visual system, each activity informing the other.

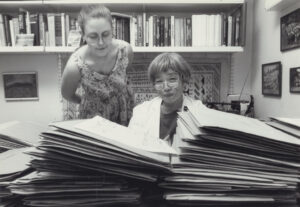

In 1982 I joined her laboratory as a Research Assistant and part time PhD student, having graduated from UCL. Hisako set the benchmark for work rate, she would be the first in in the morning and last to leave. A week consisted of a whole day clinic on Monday, experimental set up day Tuesday, followed by a forty-eight-hour experiment on Wednesday and Thursday. Fridays were filled with grant and paper writing, as well as teaching medical students. There was usually an emergency request for further electrodiagnostic tests at least once a week!

This is not to say Hisako did not enjoy life, her weekends were spent with her family in her much-loved cottage in Kent. She would host parties both in Kent and her flat in London. An enduring memory is on a trip to a scientific meeting in Florida she was keen to see the swamp alligators close up in a canoe, she had little fear!

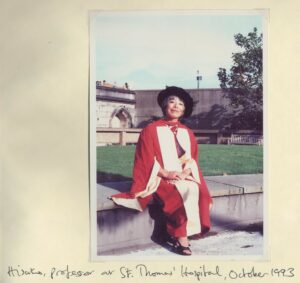

We gave Hisako a Festschrift in 1993 at St Thomas’s Hospital (Robbins 1995, ISBN978-1-4757-9364-2) and she was made Emiratis Professor of Visual Physiology and entered into the 11th edition of Marquis’ ‘Who’s Who in the World’. However, in her retirement she did not slow down, she embarked on a degrees in History of Art, Philosophy and English Literature.

In this poignant tribute from Professor Ikeda-Wolstencroft grandson, John Nicholson, John shares the story of his grandmother, a woman who followed her dream and challenged prejudices. Through kindness and generosity, she encouraged others to discover and pursue their own interests to carve out their own paths.

To Grandma, thank you for being my inspiration

Professor Hisako Wolstencroft was just Grandma to us. We knew she did an important job but didn’t really know what it was. We knew she worked hard, but she never took her professional life home with her when she was with us. All we saw was an incredibly loving, caring and fun Grandma who’d spoil us rotten, but impressed values upon us that have stayed with us since our childhood.

The biggest of which was the importance of education. Grandma was born in Japan in the 1920s, and both her parents were academics. Her father Kiguma taught English, her mother Chizu taught maths. It was extremely rare in Japanese culture for a woman to study for a degree and work as a teacher in Japan back then. I’m certain that’s where Grandma’s passion for education came from, as well as her daring attitude to break convention and stereotype. By the time us grandchildren came along, she was succeeding in a career that would have been considered impossible a few years earlier, and absolutely impossible for her in Japan. Grandma had seen what her education and upbringing had given her, and wanted the same for us.

Grandma would never push us into any particular subject or area though. She was a scientist with a daughter who played the flute for a living, and she placed just as much importance on the arts as she did academia. All she wanted for us was to learn, to find something we had a passion for, and to pursue that passion wholeheartedly. So when we announced we had a new-found enthusiasm for something – cricket, astrology, sports journalism – she’d furnish us with the equipment or books or space to do those things. It was incredibly generous, but the thing we took from that generosity wasn’t really the material gift, but the emotional support that was always there, unstinting and unapologetically biased towards her grandchildren.

Grandma looked after us almost every weekend while our parents played in concerts, driving us to the cottage she’d bought with her second husband John in the Kentish countryside. It could have been a relaxing haven away from busy London life, but Grandma didn’t see it that way. She would pretty much never stop, and her energy was infectious. I think she saw sleep as a waste of time, and she’d always be up first and wanting us to wake so we could seize the day. She didn’t like us watching TV and getting “square eyes”, so there’d always be something to do – shopping, gardening, drawing, she’d play football with us and swim with us. It ensured time with Grandma was never dull, we were never killing time and were always doing something productive.

As a migrant from a strange country, and as a woman working in a male-dominated profession, Grandma also knew how harmful and hurtful prejudice was. She placed a great importance on being polite, fair and well mannered. She loved being with people, hearing their stories and learning from their experiences. Grandma was extremely popular and had friends from all over the world, which I think tells you how kind and generous she was with everyone. She treated everyone the same. Well, almost everyone.

There’s no doubt that Grandma reserved special affection for us grandchildren. We were showered in her love, her passion and wisdom, and we’re very grateful for that. As an adult now with a family of my own, I can honestly say Grandma is my inspiration, the person I admire most out of everyone I’ve come across and been influenced by. Her story of following a dream, refusing to be blocked by society’s expectations, and above all being a kind, supportive and loving person is one I will tell to my children and will encourage them to tell to theirs. And if I can be even half the grandparent she was to us, then I’ll have done very, very well.