How a University Academy is working to improve the health and wellbeing of the local community

Professor Angus Hunter, Head of Sport Science & Professor of Neuromuscular Physiology, Nottingham Trent University, UK

Nottingham Trent University launched a health and well-being academy within its university ecosystem to tackle local health inequalities, while providing students with clinical experience. The approach, based on the model Social Prescribing, was featured in our Precision Medicine policy report. For Physiology News, Professor Angus Hunter tells us about the history and philosophy of Social Prescribing, and how the university-based academy is using the model to enhance people’s physical and mental wellbeing.

“Recognising that health and well-being are shaped by individual, social, economic, and environmental factors, Social Prescribing takes a holistic approach and empowers individuals to take control of their health. While Social Prescribing shows promise for delivering more effective preventative and rehabilitative outcomes than traditional NHS healthcare, evidence supporting its long-term effectiveness remains limited.”

Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs), particularly Type II diabetes, are on the rise in the UK1. One of the NHS’s biggest challenges is achieving sustained lifestyle changes in people to prevent and treat these diseases. Several factors contribute to this issue:

- Historical Medical Model: The NHS traditionally relies on healthcare professionals to provide solutions, such as medication and clinical treatments.

- Lack of Empowerment: This approach does not empower individuals to engage in health and educational initiatives to find solutions that work for them.

One model gaining attention to address this issue is Social Prescribing (SP). Although not a new concept, its origins can be traced back to 1926, when two Peckham-based GPs introduced a health practice that included a swimming pool, fitness centre, café, and dance hall 2, although it was not yet described as SP. Families could become members for one shilling per week (equivalent to around £5 today) and were encouraged to choose activities that suited them. Interestingly, this service was discontinued in 1948 due to lack of funding; the same year the NHS was established, marking a shift toward a more medicalised approach to healthcare.

Fostering community engagement and support networks

Today’s SP model follows a similar philosophy, connecting individuals with community services to support their well-being in non-medical ways. Health professionals refer people to non-clinical services, such as volunteering, walking groups, arts, gardening, cooking, exercise, and walking football through a link worker. Therefore, the goal of SP is to reduce social isolation, help manage chronic conditions, and promote both mental and physical health by fostering community engagement and support networks.

Recognising that health and well-being are shaped by individual, social, economic, and environmental factors, SP takes a holistic approach and empowers individuals to take control of their health. While SP shows promise for delivering more effective preventative and rehabilitative outcomes than traditional NHS healthcare, evidence supporting its long-term effectiveness remains limited.

A health and well-being academy for the local community

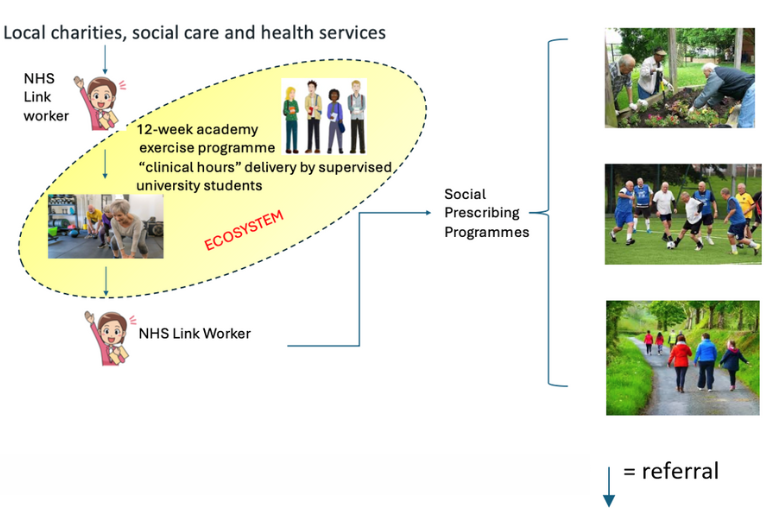

One perceived barrier to SP is that some people lack the physiological capacity and/or confidence to participate in available programmes. To address this, we launched a health and well-being academy within a university ecosystem3, aiming to tackle local health inequalities while providing students with clinical experience (Fig. 1). The academy gives sport and exercise science students valuable real-world experience to enhance their employability by delivering 12-week exercise programmes under qualified supervision.

These programmes are aimed at people referred by local NHS Primary Care Network link workers. The sessions, which take place once a week for an hour, combine cardiovascular and resistance exercises, progressing over the 12 weeks. Participants are also encouraged to do two 1-hour sessions of prescribed exercises at home each week. The programme is free, and we offer transportation for those who have difficulty attending. Then following the programme, the link worker refers the participants onto a SP programme of their choice.

Figure 1. Academy and Social Prescribing referral pathway

Boosting physical and mental health

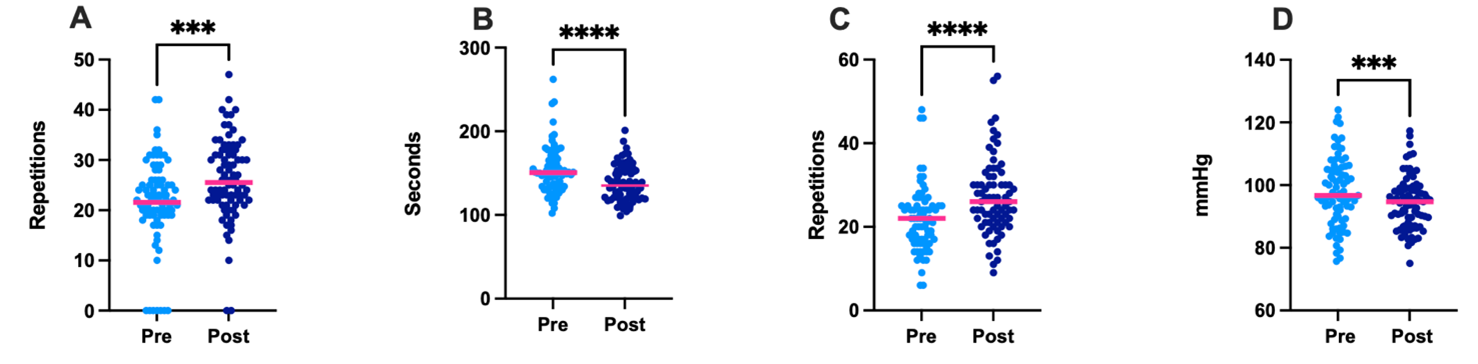

To date, our 12-week programme has shown significant benefits in functional performance, including improvements in the sit-to-stand test, local muscular endurance (measured by modified push-ups), and aerobic capacity (assessed via a 1000m cycle on an ergometer) (Fig. 2). Additionally, we observed a significant reduction in Mean Arterial Pressure (Fig. 2). Notably, the programme has an 80% completion rate, which is double the 40% typically seen in most exercise-based rehabilitation programmes4. Beyond these physiological improvements, participants have also gained the motivation and confidence to engage in social prescribing groups, where they can take part in enjoyable activities. This, in turn, increases the likelihood of long-term adherence and sustainability.

Figure 2 Pre and post 12 week academy exercise programme. A. Sit to stand 30s n=84 B. 1000m cycle n=81 C. Push Ups (modified) n=76 D. Mean Arterial Pressure n=83 **** p<0.0001 ***p<0.001

A recent Patient Participant Involvement Engagement (PPIE) session, involving SP participants and key stakeholders like NHS link workers and researchers, revealed several key outcomes. The academy model was found to:

- Provide meaningful social connections, reducing isolation.

- Improve physical activity levels, functional abilities, and self-confidence.

- Be perceived as an accessible, non-intimidating environment for individuals new to exercise.

In conclusion, the university-based academy social prescribing model holds significant potential for achieving long-term, positive health behaviour changes. However, further research is needed to evaluate its long-term efficacy and refine the model to meet our objectives.

References

- Type 2 Diabetes Prevention Week 2024: Action needed to tackle rising type 2 cases among under-40s | Diabetes UK. https://www.diabetes.org.uk/about-us/news-and-views/diabetes-prevention-week-2024-action-needed-tackle-rising-type-2-cases.

- Henry, Heather. Social prescribing : paradigms, perspectives and practice. (2025).

- Sport and Wellbeing Academy . https://www.ntu.ac.uk/study-and-courses/academic-schools/science-and-technology/sport-science/sport-and-wellbeing-academy.

- Kotseva, K., Wood, D. & De Bacquer, D. Determinants of participation and risk factor control according to attendance in cardiac rehabilitation programmes in coronary patients in Europe: EUROASPIRE IV survey. Eur J Prev Cardiol 25, 1242–1251 (2018).