2 June 1939 – 17 December 2024

By Christof Schwiening, PDN, University of Cambridge, UK

“Roger was a physiologist to the core—an enthusiastic supporter of The Society, physiology departments (even triple-barrelled ones), physiologists, and the act of ‘doing physiology,’ which always meant an experiment. He would often ‘try something out’ either deliberately or accidentally rather than spend hours deliberating potential outcomes. The approach was scientifically successful.”

In August 2024, Roger mentioned that his mitral valve was failing. His main and reoccurring complaint was of broken sleep. That email ended with the same phrase that Helen Kennedy and I exchanged, in his lab, after yet another failed experiment. It would start with “Life’s a bitch” requiring the reply, “…and then you die.” To which the first would respond, with a nod to the perpetual hell that can be electrophysiology; “If you’re lucky”.

Roger’s cardiac output remained sufficient to give a lecture to our final year students mid-October (Sodium pump). On Bonfire Night, at Monica’s invitation, we had dinner at their house, just as so many have before. There was talk of a potential mitral valve clip, but the NHS had moved too slowly. Roger knew the game was up. Neurones and nephrons require adequate superfusion; thus, Roger died on 17 December 2024 from the classic homeostatic failures he had so often lectured on.

Brian Harvey and Roger Thomas enjoying coffee in Villefranche-sur-Mer, 1987. Brian died 5 days after Roger.

I was first introduced to the concept of homeostasis by Roger, shortly after my arrival as an undergraduate in Bristol in 1984. He spoke about the concepts developed by Claude Bernard and the pithy term coined by Walter Cannon. The Bernard quote, ‘La fixité du milieu intérieur est la condition de la vie libre, indépendante’, delivered with a flourish of French. His renal lecture series involved the ‘accidental’ sip from a beaker labelled urine. We all knew it was probably apple juice, it was fun nonetheless as were the political jokes and cartoons. But, we were spared his repeated 10 min advert breaks designed to gently mock his American audiences. Roger would rarely take himself too seriously, but there was often importance to his fun, and there was a lot of fun.

Whilst listening to others, at research talks, he was always poised with a pen and notebook, or equally alert fast asleep, and would regularly ask about ‘missing scale bars’. It was his catchphrase, designed, I guess, to both lighten the mood of the audience (he knew they expected it) and ground speakers who seemed either slightly too smug or had failed to communicate clearly. It was one of Roger’s ‘serious’ games. I recently heard his post-talk questions, which I considered were based on scientific rigour, described as left-field. I sighed, probably a habit picked-up from Roger. Not everyone got it, or him.

Many of you will have known Roger from his Physiology News editorials (2015-18: PN Issues 98-110) or indeed, from his attendance at The Physiological Society Meetings over a period of >40 years (committee member, 1977-79) and his attempts to make The Society’s Annual General Meetings more democratic and fun – another serious game. He enjoyed the editorials and gently tweaking those at danger of wandering into pomposity – or threatened the things that made The Society so important to him. The voting on communications (long since abandoned), the cut and thrust of debate, the demonstrations, and the wandering around departments at small local meetings were what made The Society intellectually satisfying fun.

Roger was a physiologist to the core—an enthusiastic supporter of The Society, physiology departments (even triple-barrelled ones), physiologists, and the act of ‘doing physiology,’ which always meant an experiment. He would often ‘try something out’ either deliberately or accidentally rather than spend hours deliberating potential outcomes. The approach was scientifically successful.

As a colleague it was often annoying to find ideas discussed in the coffee room being tested, only hours later, by Roger as he was ‘playing around’ at his rig. For Roger, coffee rooms were a critical part of departmental life; they provided the interaction necessary to drive science forward. It was Roger’s speed at testing ideas that made the coffee room so valuable—coffee at 10:30 a.m. and again at 3:30 p.m. provided two opportunities each day to discuss results and plan experiments. It certainly, when accompanied by good coffee, generated a buzz.

Snails were key, they allowed for much faster iterative experimentation than any mammalian or cell culture preparation. In PN 99, Roger’s Editorial did not mention one of the critical reasons: Roger’s snail Ringer solutions contained no glucose, high energy phosphates or indeed any organics that could ‘go off’. They lasted a (very) long time.

Roger’s Ringer’s solutions only required replacing when they ran-out. The bottle on the left is dated 2007, the one next to it 2014 and on the far right 2023. They all still look good!

I took this photo a few days ago of the solutions currently above his rig. I think April 2023 (the brown bottle) was his last serious attempt at starting a new set of experiments. There is a solution dating back to 2007 (on the far left of the photo) that he would have happily used, at least after adjustment of pH. This approach meant there were always solutions ready for an experiment. It took him about 15 mins to dissect a snail, pull a few electrodes (if none were left in the beaker from the day before) and impale a neurone. This was experimentation optimised for speed and flexibility. It is something that is often missing today. But, Roger went much further with his speed optimisations. For example, in Bristol he bought a house within 100 metres (two-mins walk) of the department. In Cambridge, where such proximity was impossible, Roger still found a solution. A fellow at Downing College made him aware that a fellowship might be available. It was a perfect opportunity, Downing was only 100 metres from the lab. With lunch there most days little time was wasted and the one-mile walk home, he claimed, became a necessary part of weight control!

As Roger was often faster than anyone else at ‘getting an experiment to work’ he did not need or want a large lab. His mentoring style was simple: lead by example and encourage. He was happy doing his own experiments with typically one or sometimes two PhD students and a post-doc or visitor – of which there were many – to provide company and ideas.

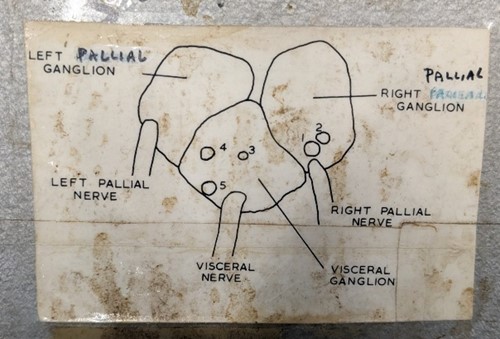

The lid to Roger’s rig was covered in aide-mémoires some going back to 1974. This drawing shows the location of some favoured cells in the snail brain.

The vast majority of Roger’s experiments used the common garden snail, Helix aspersa. They were collected locally and stored, aestivating, in a jar by his rig. When needed, he would isolate the ‘brain’—the sub-oesophageal ganglia (shown in the photo)—and mount them within a glass-fronted superfusion chamber. He would then place multiple microelectrodes into one of the many large (0.1-0.2 mm diameter) neurones. In early experiments, one microelectrode to measure membrane potential and another to add ions or pass current. In later experiments, he added additional microelectrodes (into the same cell) to allow for independent iontophoretic or pressure injection of ions, as well as voltage-clamping. This was sometimes combined with an intracellular ion sensing microelectrode (Na+, Cl–, Ca2+ or pH) and an external-surface pH-sensitive microelectrode.

Five microelectrodes inside a single cell was the limit due to the arrangement of the Prior micromanipulators, although he later made some of them double-barrelled and added other manipulators for surrounding light guides collecting calcium-sensitive fluorescence or measuring surface pH. The general philosophy being to measure and control everything, but not everywhere, all at once. The physical space limitations were both at the microscopic and the macroscopic level. Each electrode squashed the cell such that when the fifth electrode was finally driven home the cell was no longer spherical but squashed flat, or even invisible, having been pushed down into the ganglion. It was placement partly by eye, electrical signal and experience. At the macroscopic level each microelectrode holder had to miss the others as they were steered into the bath and down to the cell avoiding the pins used to hold the ganglion. And, as each electrode was moved, the others already inside the cell had to be adjusted to avoid tearing the cell membrane. It was almost impossible, hence Life’s a bitch.

While most of Roger’s scientific life (and family holidays) was spent in coastal areas—Southampton, New York, London, Bristol, New Haven, Woods Hole, Trieste—his final years (1996–2024) were spent in flat, landlocked Cambridge, where he occupied the 1883 Chair of Physiology (first held by Michael Foster) and, therefore, also served as Head of Physiology. The Physiology Department later became the triple-barrelled: Physiology, Development & Neuroscience. The additions resulting from a merger of Physiology and Anatomy, although it required multiple votes before the departments agreed. Roger would often remark that at least in Cambridge the merger was voted upon.

Roger was considered both behaviourally and ideologically an ‘outsider’ when he arrived in Cambridge in 1996 – I suspect the same was true when, in 1969, he moved to Bristol. But, Roger was no outsider to Cambridge, he was a product of its school system having spent most of his childhood there. Unlike those who were Cambridge ‘man and boy’ he arrived back, after ~40 years, with few loyalties and quickly became viewed, by those concerned with inter-departmental politics, as a potential loose cannon. When Physiology and Anatomy were encouraged to merge it was as much for pre-existing reasons as a failure to perform a hand-brake turn on the department’s finances – although, I suspect Roger’s personality did not help. He often pointed out when the king had no clothes: forthright, logical, and straightforward, before ultimately embracing democratic pragmatism.

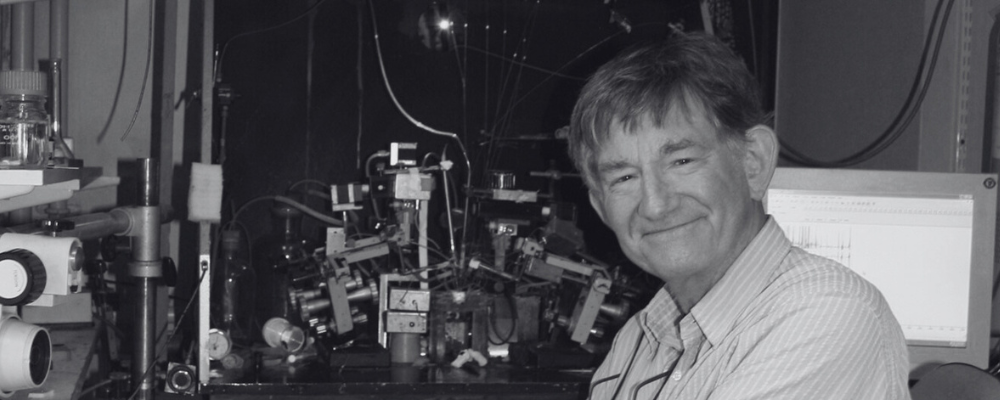

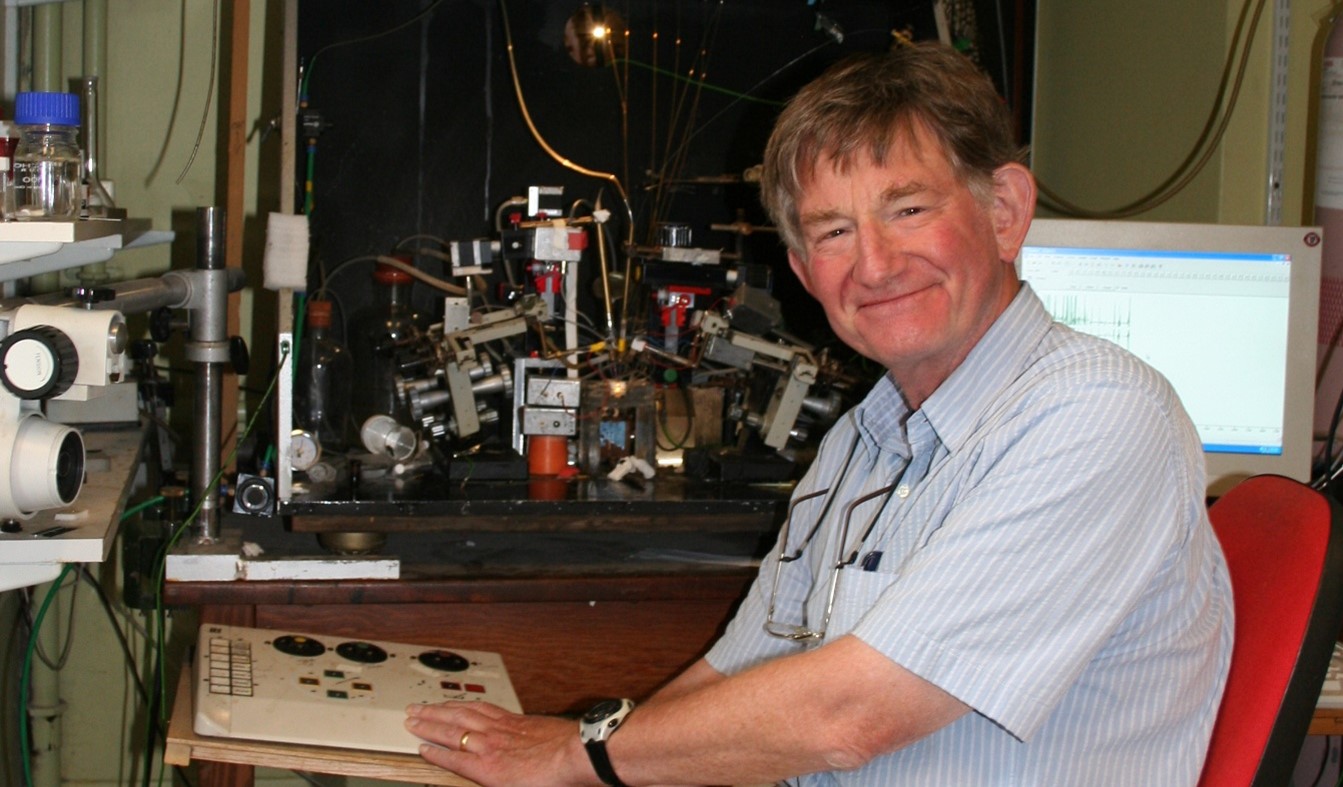

Roger at his rig. Self-portrait, July 2010.

You knew where you stood with Roger; he had a kind heart, and you had a more than decent chance of changing his mind if you presented a good argument—or, even better, some evidence. But, in general, Roger wasted little time in implementing actions following a decision. There was less than a year between meeting Monica and marriage proposal and only two weeks between marriage and departure from Southampton docks to the Rockefeller in New York. This decisiveness and speed was typical whether implementing new examination methods (MCQs or critical review papers), arranging symposia (e.g. his sudden symposium in March, 1989 proudly organised in a few hours, to celebrate his elevation to The Royal Society) or the purchase of a house or car. He was willing to take a risk.

The Lift

Roger demanded two infrastructure changes before moving to Cambridge: a new entrance area and a lift. Both, oddly, were thought controversial. The lift was even discussed at 10 Downing Street, London, although John Major was not involved.

Previously there had only been a small goods lift serving part of the rear of the building. This one (see photo) sat directly in the main staircase. Whilst Andrew Huxley, famously, took the stairs two at a time both up and down, Roger was keen that all should be able to access the building.

Speaking to people in the department in Cambridge, it is widely acknowledged that life was never dull with Roger around. He made things happen, frequently. In Bristol he organised trips for students to marine stations in Roscoff and Plymouth where a good proportion of the department (possibly more PhD students and staff than undergraduates) would decamp to do marine experiments involving Aplysia, squid or dogfish, followed by food and wine.

Lift inauguration laughter in 1997. Andrew Huxley looks on in amusement as Roger wheels Alison Brading into the new lift he had installed within the staircase of the Physiological Laboratory, Cambridge.

I was a student on one and ran experiments on many others. Roger was in his element, not least when eagerly navigating a group of us around the research station to drop in on Philippe Ascher and Richard Keynes who were in residence. The pinnacle trip, was however, his Research Workshop in the Alps. Roger had become aware that chalet rentals were cheap for a few days when the rental timetables shifted. He took advantage of that, and possibly some departmental money, to arrange a trip that even then, was frowned upon. It was a bold move. The journey back was problematic due to bad weather, which clouded Roger’s view of its success. He did not like unnecessary delay when travelling – it simply wasn’t efficient.

Roger loved to talk—or perhaps it was listen? In the tea room, at The Physiological Society meetings, over pizza or pasta, good coffee, or even when just dropping by. When he became Dean of the Faculty of Science in Bristol, he set out on what seemed to us in his lab a quest: to meet and speak to everyone in the Faculty. It was no small feat. He did the same as Head of Department in Cambridge. The Physiological Society meetings were little different— as students, we tagged along (drinks in hand), with Roger introducing us to everyone—people we would otherwise never have spoken to: Huxley, Keynes, Katz, Blakemore, Sakmann, Eccles, Neher, Withers, Tsien (times two), Young (JZ), Ashcroft, Atwell, Brading—the list goes on. Roger would always introduce us, and have some anecdote to recount. I recall Roger striding ahead of us, outside the department, towards Katz, to deliver the line “I hear you’re a building now.”

Roger was above all else, an experimental electrophysiologist for whom evidence was everything, the rest was just speculation. Quality and clarity of that evidence framed his approach to both experimentation and writing. Often that required a lot of ‘playing’ around doing things that others didn’t or couldn’t. The result, sometimes, being a chance observation which, through varied experimentation, yielded a new finding. Then came the skill of capturing it graphically. It was that process of transmitting findings, within an experimental figure, often from a complex technique that seemed to play a large part in driving him. He was rarely more pleased than when a figure of his was included within a textbook: “…elegant investigations of KERKUT and THOMAS (1963a)..” in ‘The Physiology of Synapses’ by John Carew Eccles or “…remarkable set of experiments by Thomas, using snail neurones.” In ‘From Neuron to Brain’, with the addition of an exclamation mark when describing the use of a fifth microelectrode! It made Roger beam.

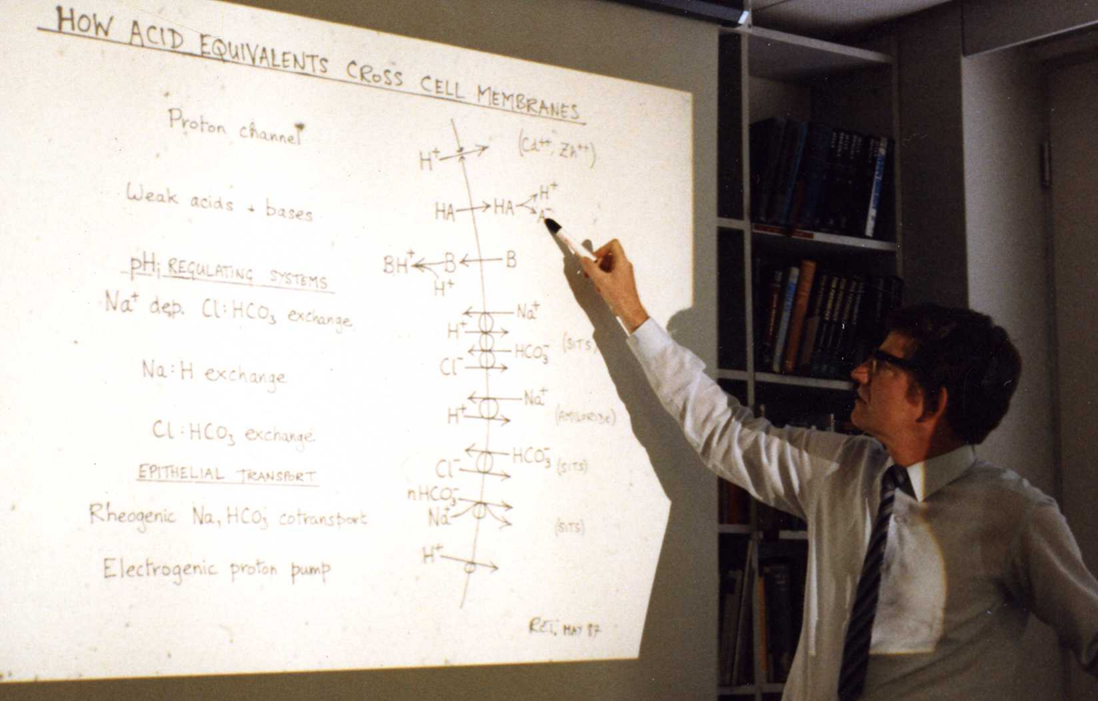

Looking at Roger’s scientific progression snails and multiple microelectrodes were key: from inhibitory receptor permeability to sodium pump electrogenicity, from sodium regulation to pH regulation and proton channels, and from calcium regulation to pH/calcium interactions.

More biographies will follow this tribute to Roger, which are due to appear in The Journal of Physiology and The Royal Society. Meanwhile, it’s a cliché he would have hated: he will be missed.