Navigating the promise, peril, and pedagogy

Dr Edd Pitt, PFHEA. Reader Higher Education, Centre for the Study of Higher Education, University of Kent, UK

“As educators, our challenge lies in balancing the significant efficiencies and opportunities AI affords with the pressing need to preserve academic integrity, critical thinking, and assessment of student learning.”

The recent emergence of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) has instigated a shift in how we think about assessment and feedback in higher education. Many have called for educators to reimagine their pedagogic practices or for assessment to be redesigned to avoid AI use or even called for outright GenAI bans within the sector. Here I expand on the keynote I recently delivered at The Physiological Society’s, ‘Challenges and Solutions for Physiology Education’ meeting, offering a synthesis of the key arguments, empirical insights, and pedagogical considerations that can shape our engagement with AI in assessment and feedback processes.

From disruption to integration: Understanding AI’s role in higher education

AI is not a monolithic entity, and distinguishing between types is essential. Weak or narrow AI typified by tools like Siri or Alexa is task-specific and reactive. Strong AI, or Artificial General Intelligence, remains aspirational but is closing the gap. In the meantime, the deployment of tools such as ChatGPT (v3.5/4.0/4.5), Copilot and Claude marks a transformative moment, where machine learning enables content generation, draft refinement, and instant feedback information. The key argument here is not whether AI should be part of higher education, that horse has already bolted and is currently running freely around the proverbial paddock! Rather how can it be harnessed ethically and effectively by educators and students alike? As educators, our challenge lies in balancing the significant efficiencies and opportunities AI affords with the pressing need to preserve academic integrity, critical thinking, and assessment of student learning.

AI literacy as a pedagogical imperative

AI literacy must now be seen as a foundational competency for both students and educators. Presently three pillars define this literacy: understanding the capabilities and limits of GenAI, critically engaging with AI-generated content, and recognising the ethical issues that surround its use. As GenAI becomes more ubiquitous, our students must be equipped to question its outputs, understand its biases, and use it responsibly, not just to complete tasks more efficiently, but to learn more deeply. As educators we must move beyond fear-based narratives. Preventing AI use is no longer plausible; rather how might it fit into our pedagogical approaches? How might we design assessments and feedback processes that incorporate GenAI as a partner in learning, not merely a threat to it?

The AI-feedback nexus: Opportunity and complexity

One potentially positive affordance of GenAI lies in feedback information generation. The traditional higher education feedback process is often time-intensive for educators, inconsistently experienced and difficult for students to decipher. GenAI tools, by contrast, can offer instant, tailored, and repeatable feedback information. However, this potential is not without caveats and requires much more from the student as an input source rather than a passive recipient of feedback information (Winstone et al, 2020).

Recent empirical evidence supports this potential. Jacobsen and Weber (2025) demonstrated that, under optimised prompt conditions, ChatGPT could generate feedback at a scale and speed far surpassing expert humans, and in some cases, with comparable quality. But and this is a big but student-initiated prompt engineering (the careful crafting of instructions given to the Gen AI) was a critical factor, high-quality iterative prompts can yield more high-quality feedback information (Jacobsen & Weber, 2025). It’s a skill our students need to develop otherwise vague inputs will result in generic or misleading outputs.

This leads to a key pedagogical shift for us as educators, feedback becomes not merely a product but a process (Pitt and Carless, 2022). Students need to learn to engage in iterative cycles of drafting, AI-supported revision, internal critique, and reflective refinement. In doing so, they begin to develop their feedback literacy; a meta-skill that fosters autonomy, critical thinking, and lifelong learning (Molloy et al. 2020).

Student perspectives: The reality of AI engagement

Early indicators from a Large-scale study involving nearly 7000 participants in Australia (Henderson et al, 2025) reveals nuanced student attitudes to Gen AI feedback information. Whilst appreciating the efficiency they expressed concerns over accuracy, depth, and the potential for overreliance. When it comes for enactment of GenAI feedback information a particularly rich area of insight comes from research into how L2 (English as an additional language) students respond to form-focused versus content-focused AI-generated feedback (Chen et al., 2024). Acceptance rates were significantly higher for grammatical corrections than for content critiques. Students were more likely to argue with or reject AI feedback information relating to their ideas, suggesting a disconnect between their intentions and the algorithm’s interpretations. The result from these emerging studies underscores the need for educators to openly and honestly discuss the transparency and contextualisation of GenAI outputs within their classrooms alongside the need for training in not just in how to use GenAI, but in how to critically respond to what it generates.

Reimagining assessment: Resistance and redesign

The dominant GenAI response dialogue across many HE institutions has been to make assessments “AI-resistant”. While some forms of assessment like oral exams or in-class performances, do limit the use of GenAI, this mindset can quickly become reductive. Instead, we might ask, what does GenAI afford that traditional assessment cannot? How can we reconfigure assignments to scaffold both student learning and ethical AI use?

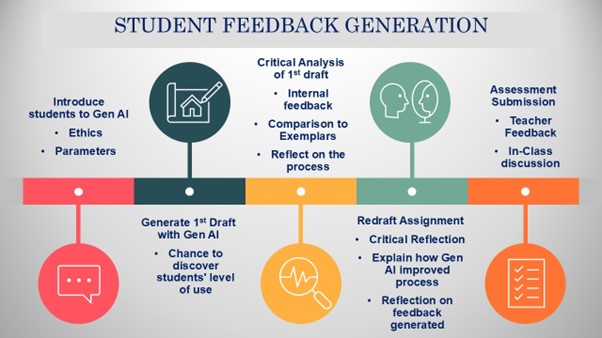

A powerful approach could involve positioning GenAI as an integrated step within the formative assessment cycle. One proposed model includes:

Such a model foregrounds student agency, criticality, and reflection, which are skills we prize in Higher Education, irrespective of technological change.

Cautions and ethical considerations

The integration of AI into feedback processes is not without danger. Overload is a real issue; too much feedback information, especially if repetitive or irrelevant can lead to student disengagement. There is also the risk of students mistaking the fluency of GenAI for conceptual understanding or deferring entirely to its authority without critical evaluation.

There are also deeper ethical questions as well. What data is being fed into these systems? How are student identities and intellectual property protected? And what are the equity implications, particularly when some students may have more access or skill in using GenAI than others? We must therefore ensure that pedagogical equity, not just technological efficiency, guides our decisions in the coming years.

Feedback as pedagogy in the age of AI

GenAI feedback information is not a substitute for human generated feedback, it can be a catalyst for reshaping how both educators and students conceptualise it. If designed with care, assessments in the AI era can do more than test knowledge, they can cultivate reflective, ethical, and critical learners. But this depends on us, as educators, being proactive: redesigning tasks, rethinking feedback processes, and reorienting our practices around student learning in a technologically saturated world. We must embrace the dynamic interplay between promise and peril, recognising that AI will only ever be as pedagogically useful as the frameworks we place around it. The future of feedback is not machine-dominated, rather it is co-constructed.

References

Chen Z et al. (2024). L2 students’ barriers in engaging with form and content-focused AI-generated feedback in revising their compositions. Computer Assisted Language Learning, pp. 1–21 https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2024.2422478

Henderson M et al. (2025). Comparing Generative AI and teacher feedback: student perceptions of usefulness and trustworthiness. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2025.2502582

Jacobsen LJ & Weber KE. (2025). The Promises and Pitfalls of ChatGPT as a Feedback Provider in Higher Education: An Exploratory Study of Prompt Engineering and the Quality of AI-Driven Feedback. AI 6, 35, pp. 1-17.. https://doi.org/10.3390/ai6020035

Molloy E et al. (2019). Developing a learning-centred framework for feedback literacy. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45(4), pp.527–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2019.1667955

Pitt E & Carless D. (2022) Signature Feedback Practices in the Creative Arts: Integrating Feedback Within the Curriculum. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education. 47(6), pp.817-829. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2021.1980769

Winstone NE et al. (2020). Educators’ perceptions of responsibility-sharing in feedback processes. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 46(1), pp.118–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2020.1748569