Dedicated to widening participation in STEM-based careers

Professor David Greensmith, University of Salford, UK

In this special issue of Physiology News we are celebrating education focused careers. Read our Q&A with David Greensmith, The Society’s 2023 Otto Hutter Teaching Prize Lecture recipient, as he shares the challenges and opportunities he’s faced on his career journey, and what he considers the most rewarding part of being an educator.

“Like many, my first permanent academic position was mixed contract, with expectations to develop research alongside a much higher teaching commitment. But this need not produce a tension, and one can actively co-develop teaching and research profiles complementarily. Indeed, I’d argue that to do so leads to a more rounded and rewarding career. It certainly provides a more direct route to make a real difference to the lives of others.”

Please tell us about your journey to where you are now. What challenges or opportunities have you found along the way?

I developed an interest in science at a very early age and for as long as I can remember, when asked “what do want to be when you grow up”, I’d answer “a scientist!”. My family always encouraged and nurtured this, for which I am grateful, but it wasn’t until university that I fully understood how to realise this aspiration.

Until then, a lack of robust career advice was an early challenge. For instance, at high school and following a brief (and only) career counselling session, I was categorically told “be an industrial chemist”. This single algorithmic output completely disregarded the considerable breadth of STEM and researched-based careers of which I was largely unaware. This is why now, I’m so passionate about high school outreach programmes that seek to raise awareness; not to disparage other career options, rather to ensure learners do not miss research-based career opportunities simply because they do not know they exist (Greensmith and Greensmith, 2025).

In my case, due to a fundamental interest in the subjects, I did progress to science-based A-levels. Yet even at college, those subjects were not fully career contextualised. My vague ambition to “be a scientist” remained, but so did my lack of career insight. And so, as I’ve never been good at working hard without a clear point to it, I didn’t do as well as I ought to have!

Nonetheless, in 2001 I arrived at The University of Salford to study Biological Sciences, and the early weeks were transformational. What still resonates most is the almost instantaneous clarity provided by meeting my lecturers, who I discovered were the type of scientist I’d always aspired to be. For the first time, I understood what academic research was and the prerequisite next steps. I set my sights on securing a PhD and never looked back.

At this point, I was most interested in plant biology. However, my interests were shifted by a series of human physiology modules then honed by a research-based placement at University Hospital Aintree. This was a pivotal opportunity in my career as the experience opened the door to a PhD then two post-doctoral positions in cardiac physiology at The University of Manchester. Here, I was supervised by Professors Mahesh Nirmalan, David Eisner and Andrew Trafford, to all of whom I owe a great deal.

Tell us about where you started in your career, what made you decide to work in physiology education?

During my postdoc, I agreed to deliver some undergraduate physiology lectures, and it was then that I realised how much I enjoyed teaching. However, the educator element of my career began in earnest in 2014 when I returned to the University of Salford as a lecturer in Biomedical Science. Here, research remained a personal and professional priority, and I established an independent cardiac research group that remains active. Nonetheless, the relatively high teaching workload permitted my parallel development as an educator.

Yet from the outset, I never saw teaching as a burden, or something that took time away from my research. Rather, I embraced and thoroughly enjoyed the various teaching delivery and leadership opportunities that presented themselves, which included the opportunity to engage in pedagogical research alongside cardiac. In 2022, I changed tack by taking up the position of Associate Dean for International Development. Here, I still teach physiology and remain involved in pedagogy research and dissemination while maintaining my interests in cardiac research.

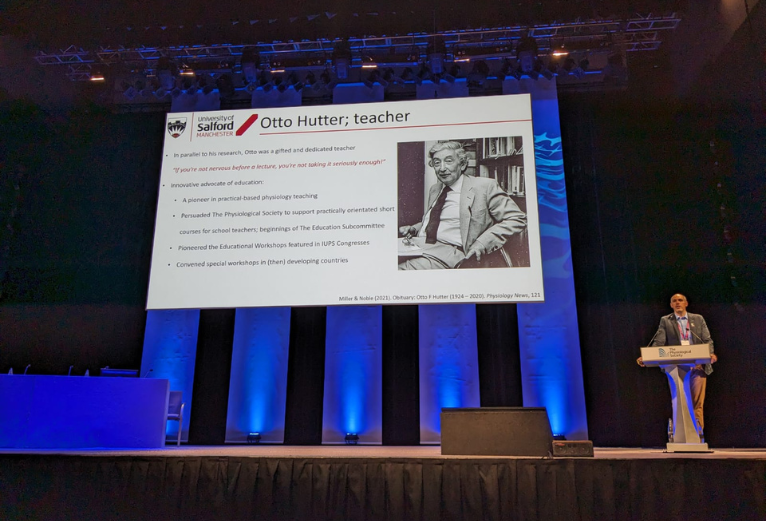

David Greensmith presenting his Otto Hutter Teaching Prize Lecture and receiving his award at The Society’s Physiology 2023 conference

What do you think is the most rewarding part of being an educator?

As a physiologist, to share my subject knowledge and watch a similar passion develop in students is inherently satisfying. But it is the opportunity to enhance widening participation in STEM-based careers that I find most rewarding, and I am a passionate advocate of students from socially disadvantaged backgrounds; an important characteristic that is frequently overlooked when considering diversity. As I mentioned earlier, school outreach can improve awareness of thus access to university. However, students who arrive from socially disadvantaged backgrounds are frequently behind the graduate capital curve, limiting career prospects.

I work as part of a team of dedicated educators who run several extra-curricular programmes that seek to enhance graduate capital thus facilitate progression to a range of STEM-based careers (Namvar et al., 2023). Here, my contribution was to establish Salford’s Research Careers Working Group, a mentorship scheme that seeks to raise awareness of research-based careers then facilitate progression to PhD through provision of insight and experience. I’m incredibly proud to have received the 2023 Otto Hutter Teaching Prize and Lecture for my contributions to widening participation in research.

How has the sector/landscape changed since you become an educator?

One trend I find encouraging is that education-based research and innovation pathways are increasingly supported and recognised by institutions and societies in meaningful ways. In this regard, The Physiological Society has for a long time been ahead of the curve, with an education and teaching theme, associated sessions at main meetings – which are now joined by dedicated two-day meetings – and The Otto Hutter Teaching Award. This trend is increasingly reflected by other societies and the career and promotion pathways within higher education.

Do you have any advice for anyone seeking to pursue an educational pathway?

It’s important to remember that pursuing education-based pathways does not mean one needs to turn ones back on research. Teaching-only contracts present opportunities to engage in pedagogical research, which is rewarding, innovative and can produce outputs that can directly improve practice. Like many, my first permanent academic position was mixed contract, with expectations to develop research alongside a much higher teaching commitment. But this need not produce a tension, and one can actively co-develop teaching and research profiles complementarily. Indeed, I’d argue that to do so leads to a more rounded and rewarding career. It certainly provides a more direct route to make a real difference to the lives of others.

References

Greensmith C & Greensmith D. (2025). You don’t know what you don’t know; using high school outreach to improve awareness of bioscience-based careers and higher education. Current Research in Physiology, 8, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crphys.2025.100151

Namvar S et al. (2023). Enhancing employability through building graduate capital: a multi-faceted approach. Contemporary practices and initiatives in employability – An advance HE case study compendium, 83-88.