The process of stopping an ongoing action could either originate from the cortex, as global suppression of the motor command regardless of the task-relevant muscles or can be triggered at subcortical levels by activation of the movement antagonists (1). Whether the action is inhibited from the start (no movement at all) or is suppressed at a later stage (stop an ongoing movement) depends on the time of the stop (2). Objective: In this preliminary study, we investigated the neuromuscular underpinnings of stopping a forward voluntary postural sway action. We predicted that the ability to inhibit forward sway is not only related to time but also to the degree of body incline at the time of the stop.

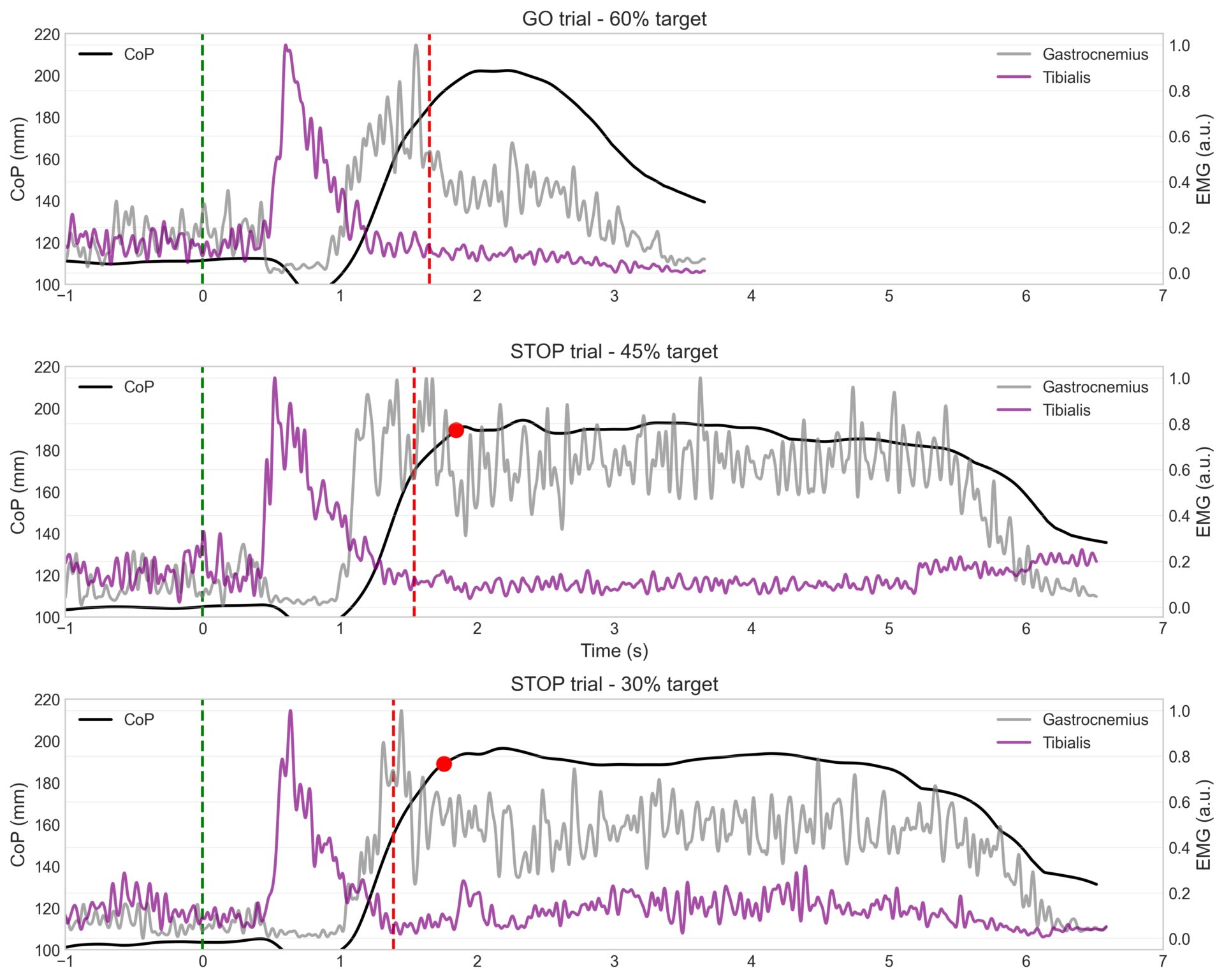

Method: The study was conducted at King’s College London in the Biomechanics Laboratory (ethics MRA-24/25-48273). Ten healthy young adults (6 males, 4 females; mean ± SD age: 30.0 ± 9.80 years; height: 172.83 ± 8.20 cm; body mass: 66.8 ± 13.03 kg; foot length: 256.67 ± 17.08 mm) stood barefooted on a force platform (AMTI OR6-7, MA, USA, 1000Hz) facing a computer monitor (1.5 m) displaying a GO (green target) and a STOP (red target) signal. Participants were fitted with surface electromyography (EMG) electrodes (Delsys Trigno Delsys Inc.,MA, USA, 2000Hz) placed over the gastrocnemius, soleus, tibialis anterior and the deltoid (reference) muscles. EMG and CoP data were synchronously sampled (Vicon Nexus, version 2.12, Vicon Motion Systems Ltd., Oxford, UK). At the onset of the GO signal, participants performed 100 forward sway trials until the CoP reached a target corresponding to 60% of maximum leaning distance. At random trials (28%), the GO target disappeared signaling a STOP, a command to halt forward sway and maintain this posture for 3s. The STOP appeared at two positions, when CoP reached 30% and 45% of the maximum leaning CoP distance. Representative CoP and EMG traces for one participant are shown in Figure 1. Stop signal distance (SSD) and stop signal reaction time (SSRT) were calculated as the distance and time between the STOP trigger and the maximum forward CoP velocity respectively. Outcome measures were compared between the two STOP positions using paired samples t-tests.

Results and conclusions: SSD was greater when the STOP was signaled at the short (30%) than longer (45%) CoP position [t(9) = 2.8, p<.05]. However, SSRT was not different between the two STOP distances (p>.05). Sway velocity at the time of the STOP was also not different between the two STOP distances (p>.05). Results suggest that the distance needed to halt voluntary forward sway depends on the degree of body incline at the time of the stop onset highlighting the importance of considering whole-body mechanics in action stopping (3) when compared to upper limb stopping paradigms.

Figure 1: Representative CoP (black) and EMG (gastrocnemius, tibialis) signals during the GO(1st row), the 45% (2nd row) and the 30%(3rd row) STOP trials. The green and red vertical dotted lines indicate the time of the GO and STOP signals respectively whereas the red dot indicates the behavioral STOP.