Introduction: Humans are able to voluntarily suppress unnecessary or unwanted actions. The neural mechanism of such suppression is thought to rely on a prefrontal–basal ganglia network. A key neurophysiological marker of this network is a global motor system suppression, characterized by a widespread, transient downregulation of corticospinal excitability during reactive stopping of voluntary actions. However, it remains unclear whether this mechanism extends to the voluntary suppression of involuntary movements.

Aims: The present study aimed to determine whether global suppression is recruited when individuals suppress a sustained involuntary movement and to further characterize the temporal dynamics of this process.

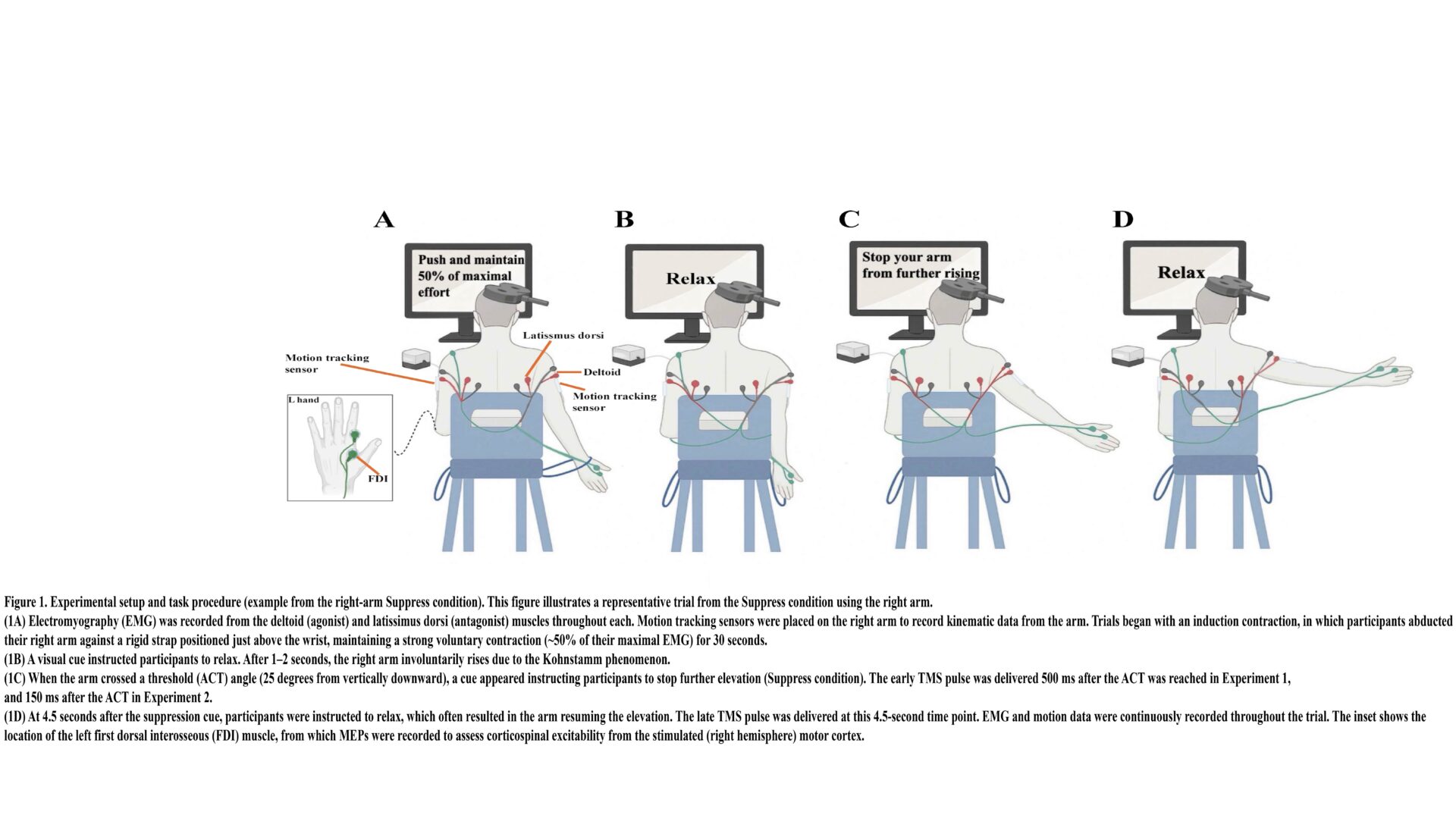

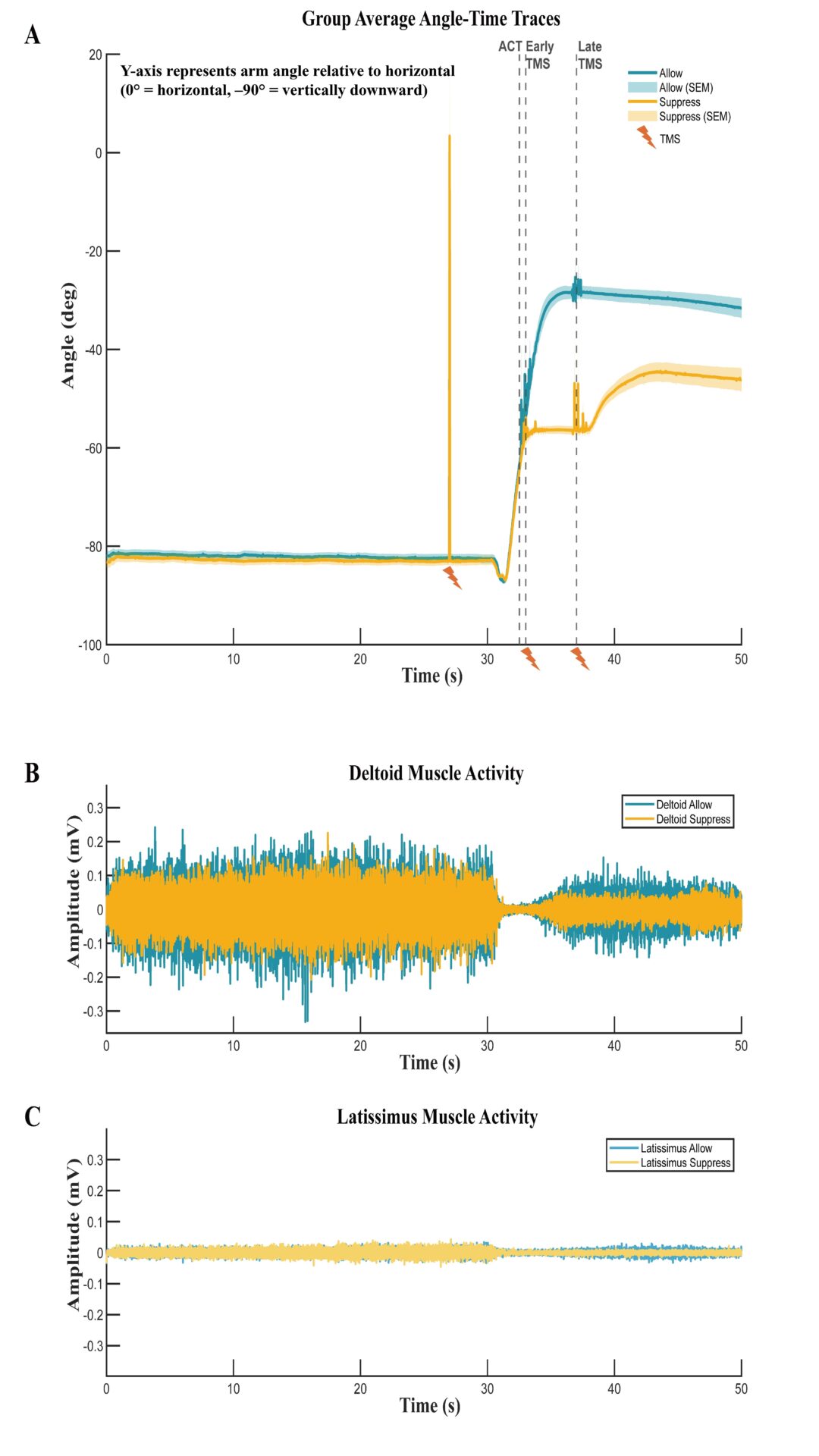

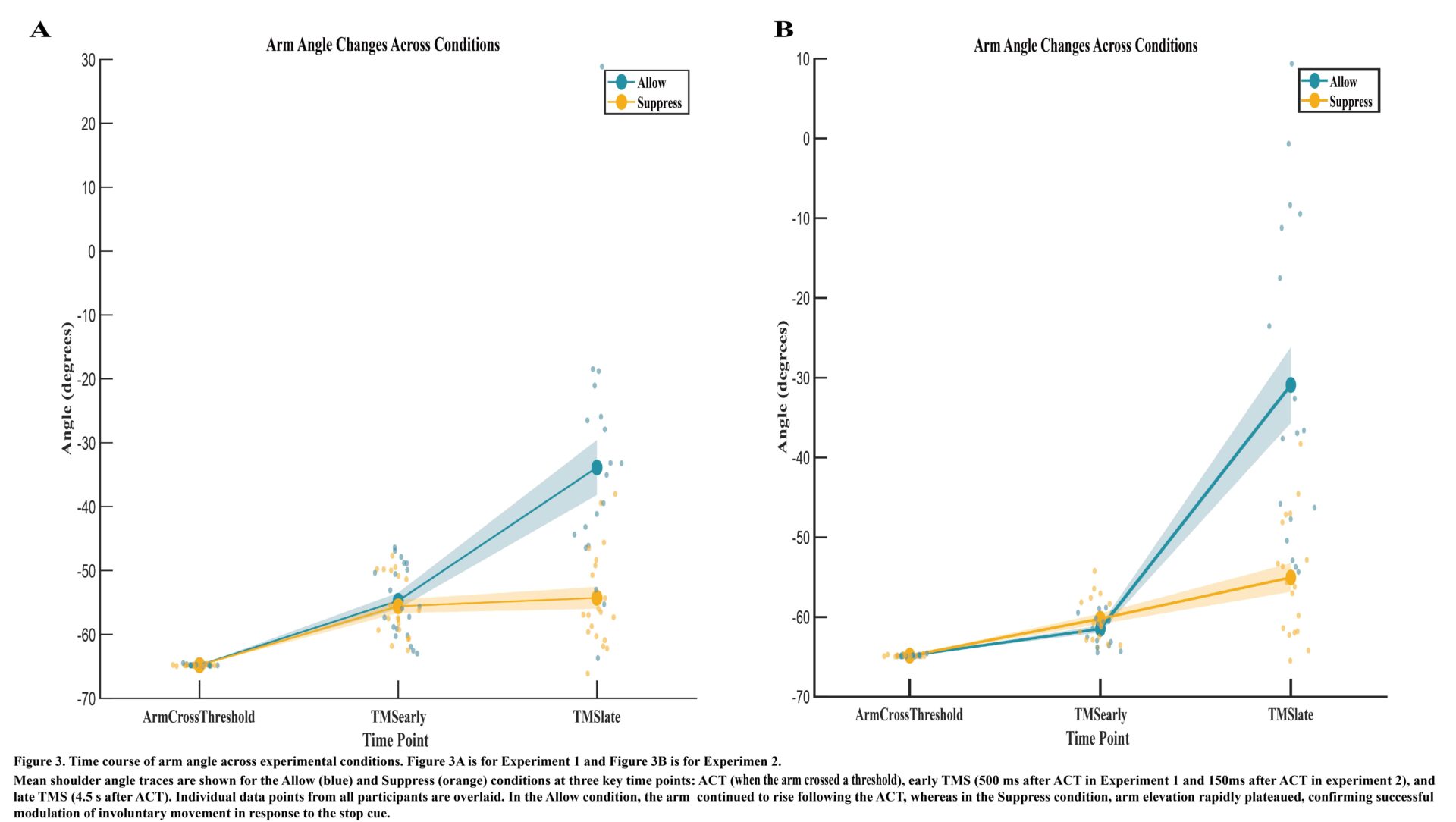

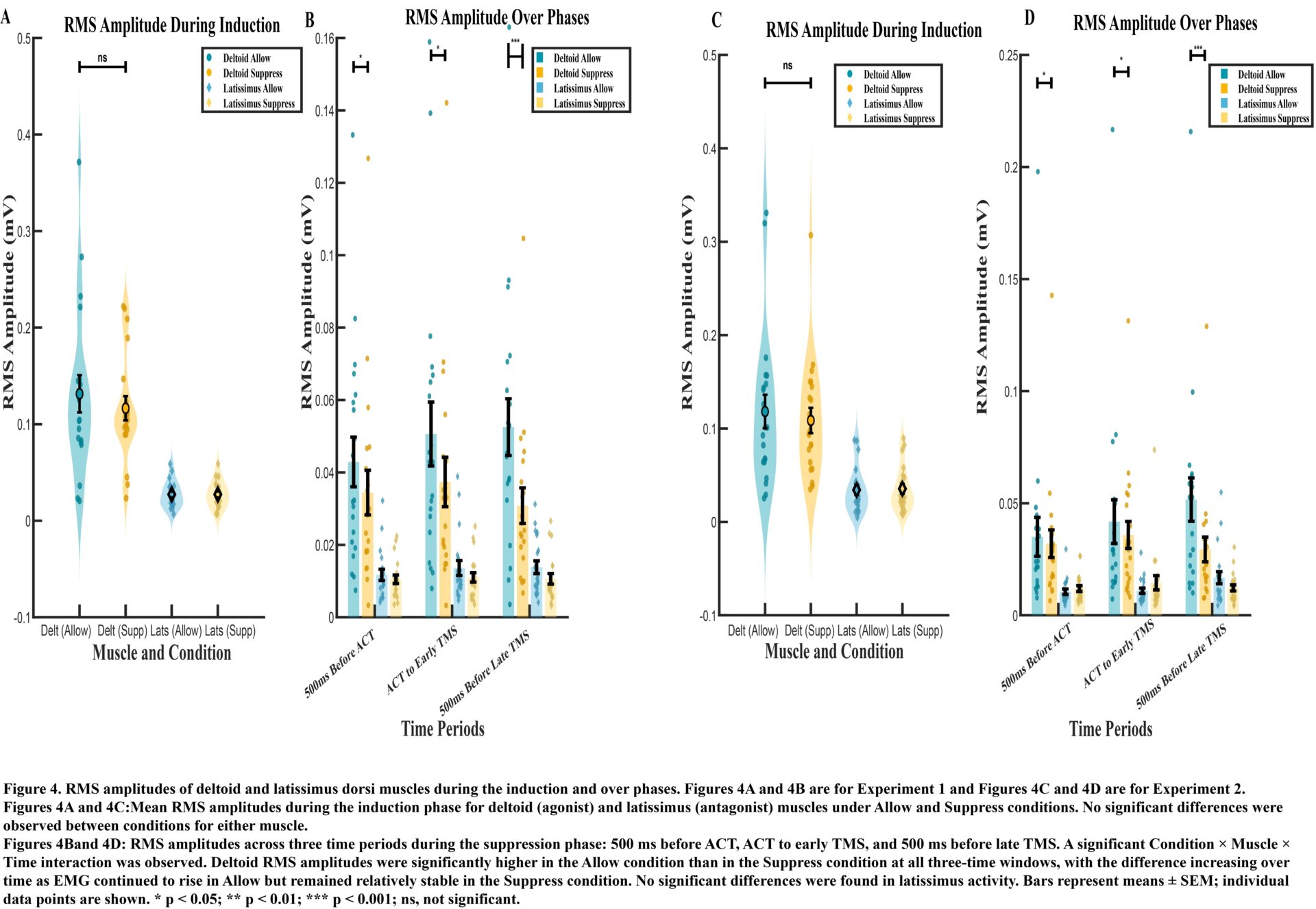

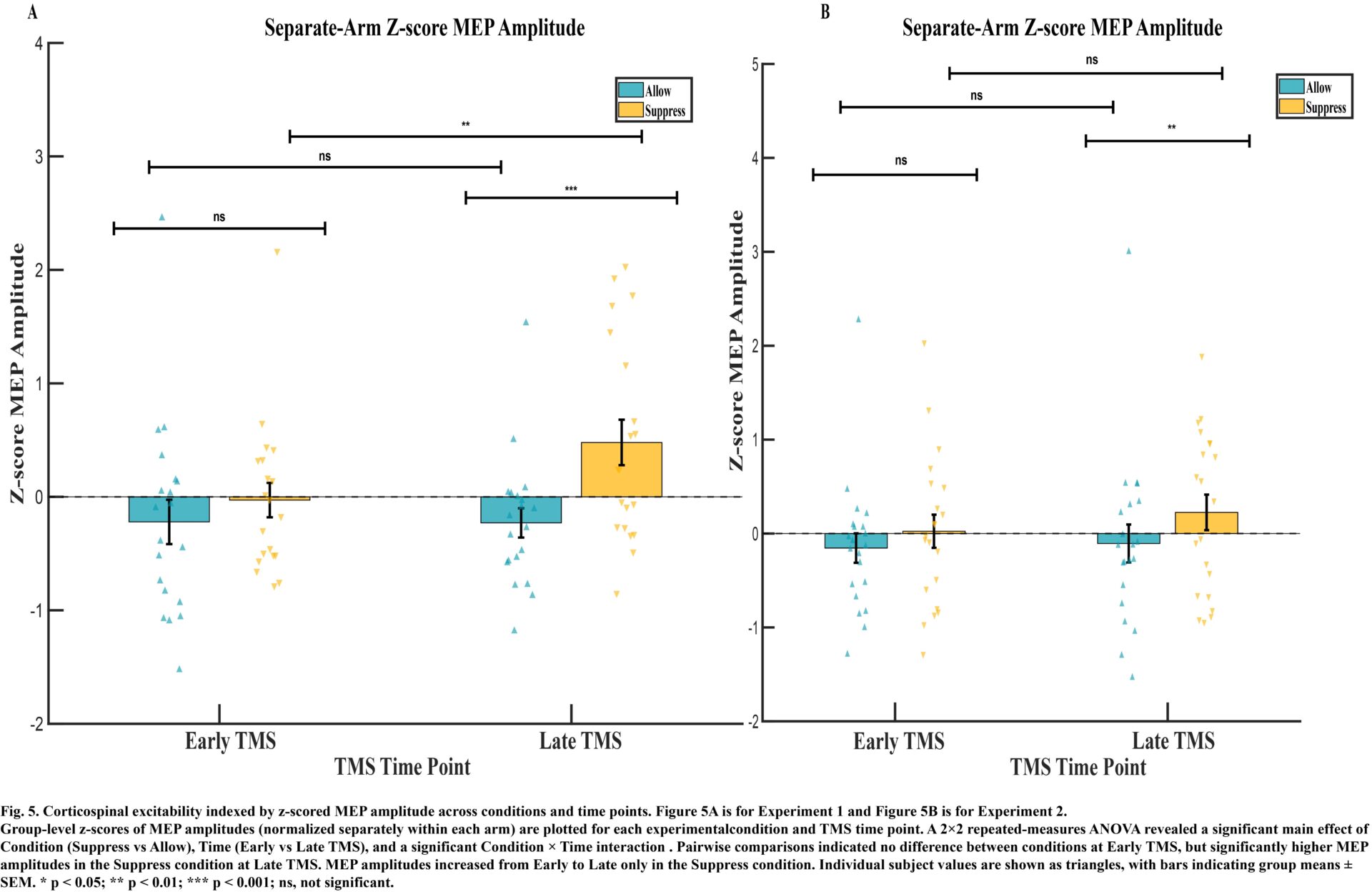

Methods: Healthy adults were recruited in two experiments: Experiment 1 (N=20) and Experiment 2 (N=18). The Kohnstamm phenomenon, defined as involuntary arm elevation following sustained deltoid contraction, was used as a model of involuntary movement. In a within-subject design, participants either allowed the involuntary drift to occur naturally (Allow condition) or voluntarily suppressed it following a stopping cue (Suppress condition). To probe global suppression, motor-evoked potentials (MEPs) were recorded from a contralateral, task-unrelated muscle (first dorsal interosseous, FDI) using single-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). Two stimulation timings were employed: early TMS, delivered shortly after the arm crossed a threshold angle (ACT) (500 ms in Experiment 1; 150 ms in Experiment 2, the latter consistent with the latency of global suppression in reactive-stopping paradigms)1,2, and late TMS, delivered 4.5 s after ACT. Arm kinematics were continuously tracked and extracted at ACT, early TMS, and late TMS. Electromyography (EMG) was recorded from the deltoid and latissimus dorsi; root mean square (RMS) amplitudes were calculated and compared across the induction phase and three critical epochs (500 ms before ACT, ACT–early TMS, 500 ms before late TMS). ANOVA was conducted to analyse condition by time interactions for arm position, EMG and MEP amplitudes.

Results: Behavioural and EMG analyses confirmed that participants successfully suppressed involuntary arm elevation (Condition × Time interaction: Exp.1, F(2,38)=31.87, p<.001; Exp.2, F(2,34)=38.80, p<.001), primarily through control of the agonist deltoid – preventing the rise in agonist activity (Condition × Time interaction: Exp.1, F(2,38)=4.03, p=.028; Exp.2, F(2,34)=25.10, p<.001), Condition × Time interaction: Exp.1, F(2,38)=1.67, p=.202; Exp.2, F(2,34)=3.87, p=.058). However, MEP analyses revealed no evidence of global suppression: at no timepoint were MEP amplitudes lower in Suppress than in Allow. A significant main effect of Condition was observed in both experiments (Exp.1: F(1,19)=13.73, p=.002; Exp.2: F(1,17)=21.21, p<.001), whereas the Condition × Time interaction reached significance only in Exp.1 (F(1,19)=7.30, p=.014). At early timepoints, no significant differences appeared (Exp.1: t(19)=-1.47, p=.158; Exp.2: t(17)=-1.94, p=.068). Indeed, at the late timepoint, MEPs in Suppress were consistently greater than in Allow (Exp.1: t(19)=-4.04, p<.001; Exp.2: t(17)=-2.52, p=.022), indicating that sustained suppression was not accompanied by widespread cortical downregulation.

Conclusions: Across two independent experiments, we consistently found that voluntary behavioural suppression of sustained involuntary movement does not depend on neural global suppression mechanism. Instead, behavioural suppression may be achieved through selective neural suppression of the primary agonist muscle representation.