By Benecia Wong, Liz Blanks, Alireza Mani (University College London (UCL), UK)

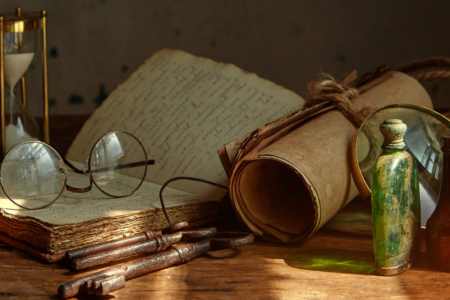

The UCL Historic Objects and Collections series presents Physiological Instrument #016, Bárány’s Soundbox. In this series, the team tell the stories of physiological artefacts housed in the institute’s rich collection. The first object on display is a soundbox, a clockwork device from the early 1900s to test hearing.

A clinical tool in otology

Robert Bárány (1876–1936), an Austrian Nobel laureate, pioneered the foundations of modern neurotology through his groundbreaking discoveries about the vestibular system, the inner ear system that helps maintain balance and spatial orientation. Bárány refined diagnostic techniques that tested balance, orientation and inner ear function in an era of science where the investigative techniques were poor. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1914, recognised for his research on physiology and pathology of the vestibular apparatus, specifically in relation to dizziness, vertigo, and inner ear disease.

One of his lesser-known but clinically significant innovations was the development of a noise-generating device, often referred to as Bárány’s soundbox. An example of this device resides within UCL’s History of Science Collections (Figure 1). The museum collections showcase the development of scientific fields throughout the university’s 200-year history. In 1836 William Sharpey became the first Professor of Anatomy and Physiology. His tenure lasted nearly 40 years and earned him the title of ‘the father of modern physiology’ in Britain.

Sharpey began a long legacy of pioneering academics teaching physiology as a means of providing Medical School students with a foundation in the sciences. UCL became the seminal place for the study of the subject during the early part of the 20th century. The soundbox would have originally facilitated study within the department and is now part of object-based learning sessions focused on the history and development of this discipline.

Though the original intention was to study auditory masking and auditory-vestibular interactions, the device gained recognition for its unexpected value in clinical otology and psychiatry. Bárány’s soundbox thus became a diagnostic tool for conditions such as malingering and conversion disorder, in which deliberate or unconscious suppression of voice or hearing can be assessed through a person’s response to auditory masking. Its application provided primary insight into the complex interplay between auditory feedback loop, vocalisation, and psychological factors, and it remains a historical milestone in the evolution of functional diagnostics in otolaryngology and neurology.

Figure 1. The Bárány soundbox (LDUSC-PHYSIO-016).

How does it work?

The Bárány Soundbox is a mechanical noise-making instrument which connects to one ear canal. It was initially developed to allow the distinction between unilateral and bilateral deafness, as when placed in the ear with hearing, there is a detectable change in speech volume and when placed in the deaf ear, there is no change in voice phonation.

The noise produced by the box masks the patient’s own voice and external sounds, disrupting the auditory feedback loop that monitors and adjusts speech, and thereby inducing the Lombard effect, which causes an instinctive increase in vocal intensity to override the noisy environment [1]. For example, when you have your earphones in, you unconsciously speak louder. Allowing us to distinguish between patients of normal, healthy hearing and true deafness, where the patient does not compensate for the environmental noise.

The Soundbox successfully tests the integrity of auditory feedback and confirms whether the hearing loss is organic or functional, whilst being an accurate malingering detector as involuntary voice raising cannot easily be faked. The soundbox also aids with the diagnosis of disorders such as psychogenic aphonia [2], a functional voice disorder where an individual’s vocal cords are neurologically and structurally intact, but the patient is unable to speak or only whispers.

Development of the Bárány Soundbox

Bárány’s first mention of his noise box appears to be in Zeitschrift für Ohrenheilkunde (Translation from German: Journal of Otology), 1908, volume 56, pages 287–288, in an article titled “Lärmapparat zum Nachweis einseitiger Taubheit” [3], which translates to “Noise apparatus for the detection of unilateral deafness.” The origin of the ‘Lärmapparat’ (Soundbox) was due to the frustrations that arose during Bárány’s clinical observations of patients who were either unreliable or could not cooperate during hearing tests.

One of the earliest recorded uses of Bárány’s noise box in the English-language medical literature appears in a meeting of the Royal Society of Medicine in 1912, where Dr. J. Dundas Grant (A consultant at the Royal Nose Throat & Ear Hospital, now part of UCLH) discussed its application in the differential diagnosis of a patient with complete bilateral deafness [4]. His innovation marked one of the earliest uses of masking in audiological testing, laying the groundwork for modern audiometry.

Historical context of Bárány’s scientific life

Bárány was at the peak of his scientific work when World War I broke out in 1914. When Austria-Hungary entered the war, he saw an opportunity to further investigate his ideas by studying brain-injured soldiers. He volunteered for medical service and was assigned to the fortress of Przemyśl, where he was responsible for the care of ~123,000 soldiers. The fortress was a strategically critical location for the Austro-Hungarian army on the Eastern Front and became the site of one of the longest blockades during the war from September 1914 to March 1915.

During this time, many soldiers suffered from head injuries due to artillery and trench warfare, allowing Bárány access to a unique patient population for studying neurological damage and vestibular dysfunction. He established an otolaryngology unit and developed a highly effective technique for the primary suturing of head wounds [5].

In April 1915, Bárány was captured by advancing Russian forces and taken prisoner. Although he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1914, the presentation was delayed due to the war and his imprisonment [5]. His capture came at a time when prisoner exchanges were uncommon, and communication across enemy lines was limited. With the help of Prince Carl of Sweden and negotiations led by the Swedish Red Cross, Czar Nicholas II agreed to release Bárány, highlighting the importance placed on scientific achievement even amid global conflict [5]. He formally received the Nobel Prize in 1916 and delivered his Nobel lecture on 11 September of that year.

Bárány’s Nobel Prize lecture and contribution to physiology

Bárány’s Nobel Prize lecture [6] highlighted his discovery that thermal stimulation of the semicircular canals induces convection currents in the endolymph (the fluid inside the inner ear), producing characteristic eye movements (nystagmus) and balance responses. This non-invasive technique, known as the caloric reflex test, remains a cornerstone of clinical vestibular examination. He explained: “The caloric reaction method which I discovered was the first to bring light into this obscurity. Only after its discovery was a methodical examination of the function of the semicircular canals made possible”. [6]

Bárány’s breakthrough arose from chance observation, hypothesis-driven reasoning, and systematic experimentation. While flushing a patient’s ear with cold water to remove wax, he noted involuntary eye movements (nystagmus) and dizziness. From this, he concluded:

- Cold water causes the eyes to move toward the irrigated ear.

- Warm water causes them to move away.

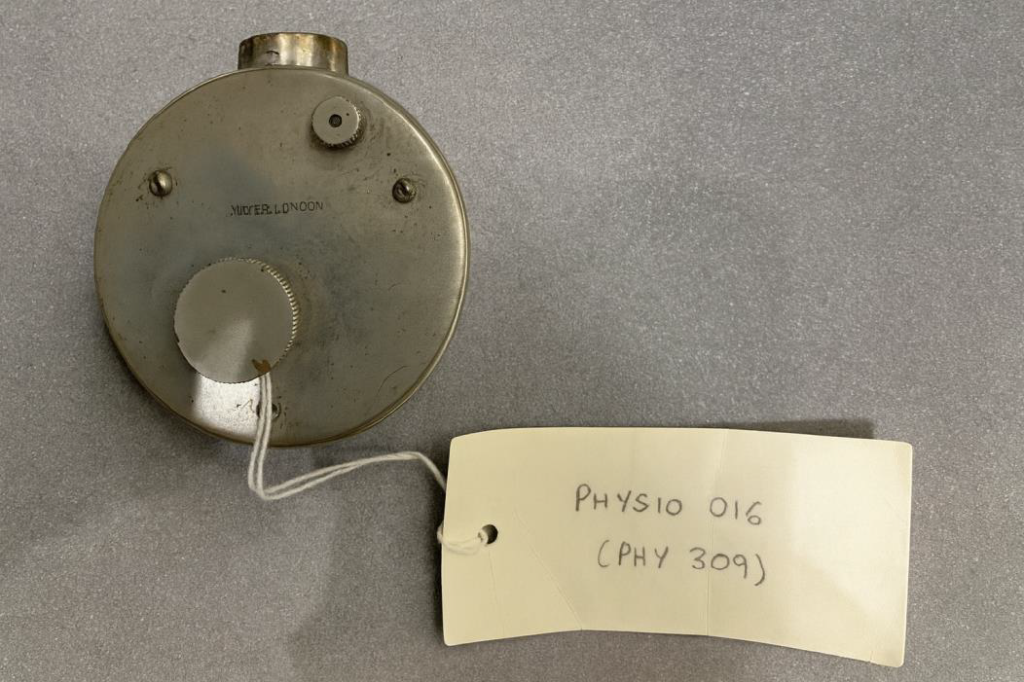

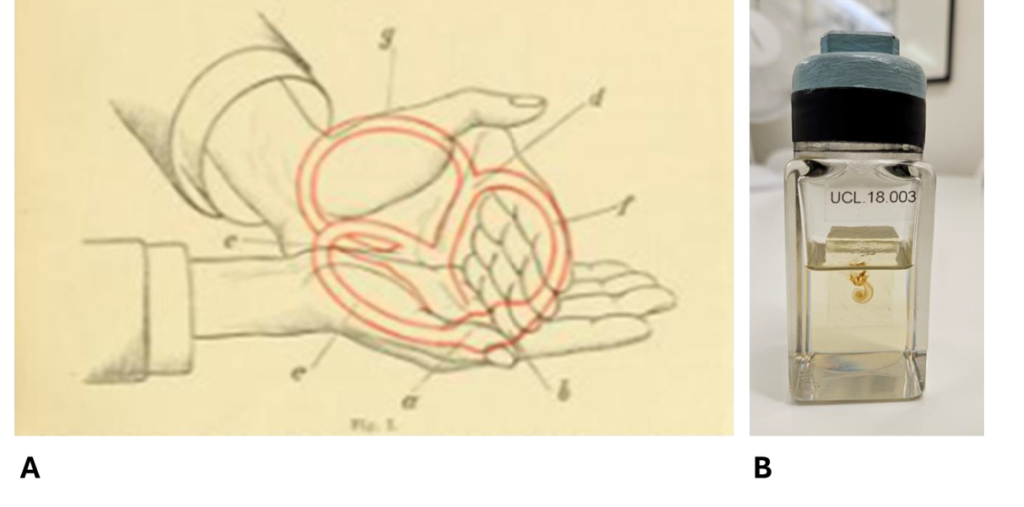

He recognised that water temperature altered endolymph flow in the semicircular canals (Figure 2), stimulating the balance organs and triggering neural reflexes. Infections such as otitis media or labyrinthitis could blunt or abolish these responses, revealing vestibular dysfunction.

Bárány’s work established that the vestibular system (a network of inner ear sensors, brainstem nuclei, and cerebellar circuits) integrates head motion and position to maintain balance, posture, and stable vision. The functional neural connection between the vestibular system and the eye muscles stabilizes gaze during head movement, while the link between the vestibular system, cerebellum, and spinal cord coordinates body posture. Bárány demonstrated that balance depends not only on signals from the inner ear but also on cerebellar processing, which refines reflexes to produce coordinated and adaptive responses. Through meticulous clinical research, Bárány transformed vague theories into precise diagnostic methods, advancing both neuroscience and medicine.

Figure 2. A. The structure of the semicircular canals as illustrated in a book published by Robert Bárány in 1907 [7]. The position of the hands indicates the relative orientation of the three semicircular canals. These canals are filled with a liquid (endolymph) and act as sensors for the spatial position of the head in three-dimensional space. B. A real specimen of the inner ear, displayed at the UCL Pathology Museum (UCL 18.003).

Bárány’s sound box has been replaced in modern practice by calibrated electronic devices used in audiometry. In contrast, Bárány’s caloric test remains a standard component of vestibular function testing and continues to play an important role in clinical diagnosis. Nevertheless, this historic apparatus is valuable for illustrating the evolution of ideas that shaped our current understanding of the auditory and vestibular systems. It also remains useful in neurophysiology-focused object-based learning sessions, alongside other instruments in UCL’s History of Science Collections, such as Francis Galton’s whistles, which were developed to explore the frequency limits of human and animal hearing.

References

- Luo J, Hage SR, Moss CF. The Lombard Effect: From Acoustics to Neural Mechanisms. Trends Neurosci. 2018 Dec;41(12):938-949. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2018.07.011.

- Dundas-Grant J. Case of Functional Aphonia, Voice restored by application of Negus’s Hand-pressure and Bárány’s Noise Machine. Proc R Soc Med. 1924;17 (Laryngol Sect):10. doi: 10.1177/003591572401700704.

- Bárány R. Lärmapparat zum Nachweis einseitiger Taubheit. Zeitschrift für Ohrenheilkunde 1908;56:287–288.

- Grant JD. The Voice-raising Test with Bárány’s Noise Machine. Proc R Soc Med. 1912;5 (Otol Sect):154-5. doi: 10.1177/003591571200501169.

- Bracha A, Tan SY. Robert Bárány (1876-1936): the Nobel Prize-winning prisoner of war. Singapore Med J. 2015 Jan;56(1):5-6. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2015002.

- Bárány R. The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1914. NobelPrize.org, www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1914/barany/lecture/.

- Bárány R. Physiologie und Pathologie (Funktions-Prüfung) des Bogengang-Apparates beim Menschen: Klinische Studien. Leipzig: F. Deuticke, 1907.