Physiology News Magazine

Letter to David Hubel

To mark the death of the Nobel Prize winner and Society Honorary Member, we here present a tribute to David Hubel by his scientific partner, Torsten Wiesel. This was presented at a memorial event at Harvard University, USA, 16 November 2013.

Membership

Letter to David Hubel

To mark the death of the Nobel Prize winner and Society Honorary Member, we here present a tribute to David Hubel by his scientific partner, Torsten Wiesel. This was presented at a memorial event at Harvard University, USA, 16 November 2013.

Membership

https://doi.org/10.36866/pn.94.46

Dear David,

I am writing these words not to say farewell but to point out that you will always remain in my heart and mind as one of the best things that ever happened to me. Even more amazing is that our 20 years working together happened completely by chance. As you well remember, your move to the department of physiology at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine was delayed because of lab renovations and that Vernon Mountcastle asked Stephen Kuffler at the Wilmer Institute in ophthalmology, where I was a postdoc, if you could be with his group for a year. Steve was delighted and the three of us met. None of us would have guessed how much that lunch meeting would change everything for us, as you and I over many cups of coffee that day began to carve out our future scientific course.

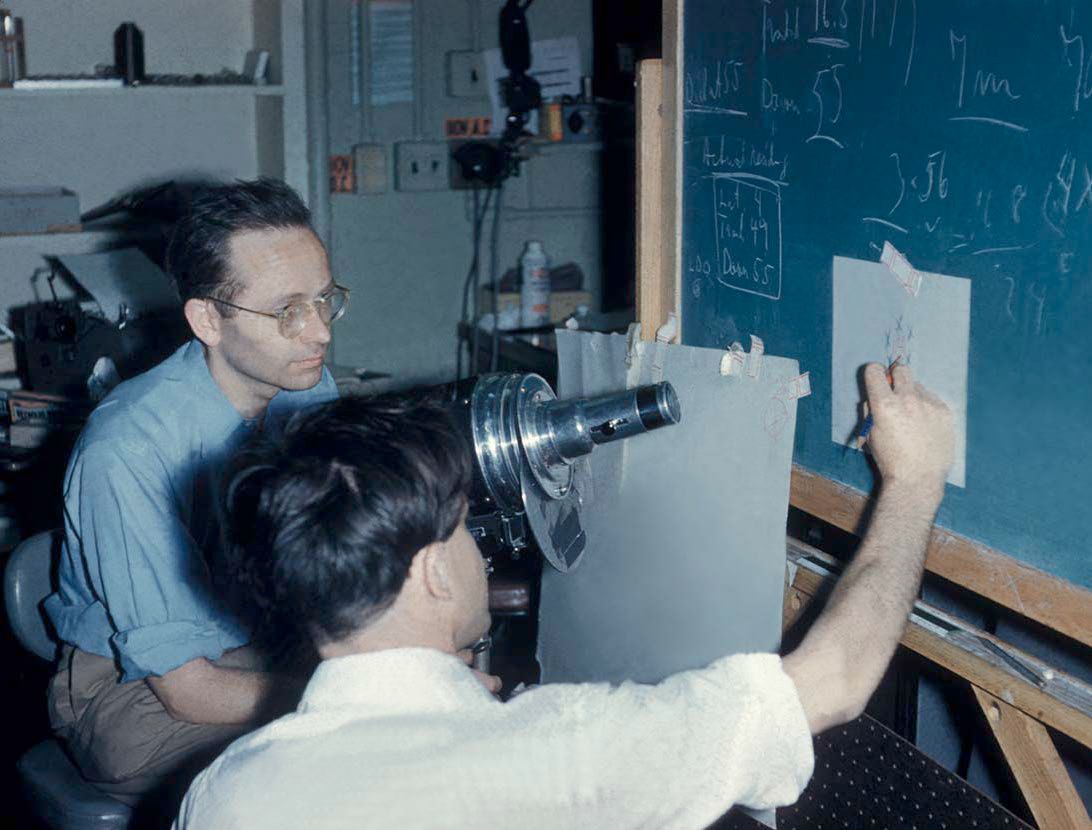

For inexperienced me, having just arrived from Sweden, you were as a gift from heaven coming with your famous tungsten microelectrode, which you had successfully used to record single visual neurons in the awake cat, made possible by elegant chambers machined on your lathe and mounted on the animal’s head (a method subsequently copied by colleagues from all over the world). Of course, more than all these technical and inventive skills you came with a brilliant and creative mind.

Our real bonding was probably established while still at Hopkins when at dawn we would go down through dark tunnels to the animal quarters to pick up a cat or monkey to be anaesthetized and later prepared for the experiment. You often like to tell the story when a spider monkey, to our amazement, skillfully used its long tail to pull the syringe with the anesthetic out of my hand as I tried to make the injection in its abdomen. You were also amused when in late night experiments I resorted to speaking Swedish.

These often more than 24 hour experiments were indeed tiring, but the long hours gave us time to get to know each other well and, above all, to explore ideas for future experiments and approaches. We were lucky to, over and over again, get exciting leads from our experiments, which in turn led to new questions and answers. Looking back on the years at Hopkins and Harvard, experiments felt like great adventures, with you rushing down the corridors screaming ‘Come and look at this amazing cortical cell responding only to a contour of a given orientation!’, and again when we found binocular cells and discovered the columnar organization of the visual cortex. We no doubt will always treasure those days and moments, which nothing can ever match. You must agree that those were the ‘golden days’. You used to say that it was like rolling yarn into a big, beautiful ball.

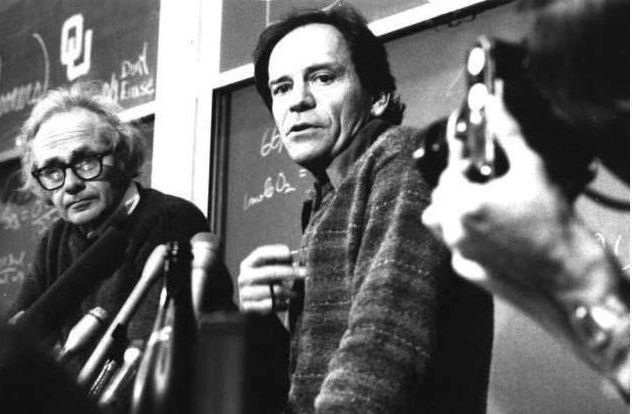

Your ability to write so eloquently is without question that of a true master. This is in part due to your love of the English language – Fowler’s Modern English Usage and other books on writing were always on your desk. You will remember the press conference after the announcement of the Nobel Prize, when I emphasized that from the very beginning your writing was critical for the understanding and acceptance of our papers.

You were always the messenger and your talks and lectures about our work are still famous for their clarity and brilliance. I must have heard your presentations of our work countless times and I still enjoyed them time after time.

You also had an amazing talent and passion to communicate, not only about our work, but the many other wonders of nature. You may remember when we visited a small sea resort outside Tokyo in the seventies when 20 or so students came around and you completely charmed them by speaking English and some broken Japanese. Actually, after a fierce effort, you became proficient enough to give a lecture in Japanese. Your passion for engaging with young students kept you yourself youthful. Many Harvard college students over the years have had the joy to listen and talk with you about science and many other interests.

For so many years we experienced the absolute wonder and excitement of discovering something that nobody else knew. Now we must leave it to the next generation, to probe into the secrets of nature yet to be revealed.

Looking back on our years together you will always remain my much admired and beloved scientific brother.

Thank you,

Torsten