Physiology News Magazine

Obituary: Joseph Fairweather Lamb FRSE

1928 – 2015

Membership

Obituary: Joseph Fairweather Lamb FRSE

1928 – 2015

Membership

Jim Aiton, Eric Flitney, Bob Pitman & Nick Simmons

Images in this article provided courtesy of the Lamb family

https://doi.org/10.36866/pn.101.40

Joe Lamb is fondly remembered within the community of The Physiological Society as one of its most prominent members, being awarded Honorary status in 2005. He held the Chandos Chair of Physiology and was Head of the Department of Physiology & Pharmacology at St Andrews University from 1969 until his retirement in 1993. He served on the Editorial Board of The Journal of Physiology (1968-1974) and became Senior Secretary of the Executive Committee from 1982 to 1985, missing out the ‘apprentice’ position of Meetings Secretary. Joe was elected Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1985.

Joe was born into farming stock in Angus. His early education was at Auldbar Junior School and then Brechin High School. He was conscripted into the RAF in 1947, under wartime regulations, and for two years worked on aerial design and maintenance at Bletchley Park, before commencing his medical training at the University of Edinburgh. He held house jobs at the Dumfries & Galloway Hospital and at the Eastern General Hospital in Edinburgh. Joe’s career as a physiologist began in earnest via the final year intercalated Honours course at Edinburgh, followed by a junior Research Fellowship. He was appointed Lecturer in Physiology at the Royal Dick Veterinary College (1958-1961) where he completed his PhD. He then moved to Glasgow University and was promoted to Senior Lecturer in Physiology (1961-1969) before leaving to take up the Chair of Physiology in St Andrews.

Joe had an infectious enthusiasm for research and was always excited about the next experiment. His research was in cardiac physiology with a particular interest in the mechanism of action of cardiac glycosides at the cellular level. His PhD dealt with the relationship between electrical activity and ionic gradients in isolated tissue, most notably with intracellular Cl. Later, in Glasgow, he and John McGuigan worked with superfused ventricular tissue and showed that mechanical effects on the extracellular space during the cardiac cycle greatly exacerbated the difficulty of making accurate measurements of intracellular ions and membrane fluxes. It soon became apparent that a reductionist approach using a simple cell system would be needed to overcome these problems. Joe was the first physiologist to introduce cultured chick heart cells grown on glass coverslips for this purpose. The important advantages of rapid exchange and ease of ion flux measurements achieved by this means came at the expense of some cell de-differentiation. The latter was circumvented later by the use of isolated myocytes and stem-cell derived cultures. In St Andrews, Joe became increasingly interested in cardiac glycosides and their well-known, but poorly understood, narrow therapeutic profile. In seminal studies using established human (Giradi and HeLa) cell lines he investigated the short- and long-term effects of cardiac glycosides, such as ouabain and digitalis. Treating cells with ouabain at therapeutic levels raised intracellular [Na] and during prolonged exposures led to up-regulation of cellular Na-pump density. Similar long-term effects were seen with ethacrynic acid or lowered external K. The increased pump density was prevented by blocking mRNA and protein synthesis, providing the first direct evidence for genetic regulation of Na-pump density by intracellular cations. The response to ouabain turned out to be complex, involving the internalisation of existing Na pumps to vesicular endomembranes, release of cardiac glycoside on vesicular acidification and recycling of Na-pumps to the plasma membrane, together with newly synthesised Na pumps.

Joe’s career took him from the highly respected Institute of Physiology in Glasgow to St Andrews where physiology was still taught to medical students despite the separation from Dundee but where research activity was limited. Joe was steadfast in his desire to do what was best for his staff and his department. He was loyal to his colleagues and their students, backing their research activities through the ‘class grant’ that always seemed to be overspent. The atmosphere in the department was congenial and a vibrant research culture was fostered in which morning coffee and afternoon tea became opportunities for wide-ranging discussions of new ideas and experiments. The number of research staff (post-docs and students) increased progressively, backed by an active seminar programme, amply fortified by post-seminar buffets from a local delicatessen. Bob Goldman, Alan Cuthbert and Mike Berridge were recipients of the ‘University of St. Andrews Visiting Lectureship’ and each delivered an intensive series of lectures to staff, research students and undergraduates. Joe’s ability to procure new lectureships was key to the expansion of the research base, so that the mean age of staff in the 1970 and 80s was comparatively young. Several (Jim Aiton and Nick Simmons) benefitted greatly from the superb tissue culture facilities, where media were made to order and vast quantities of glassware were sterilised and recirculated each week by a dedicated technical team.

Joe was equally committed to delivering high quality teaching and education. The department had high student-staff ratios in the early years, which meant that each staff member had to plan and deliver lectures on several topics, not necessarily related to his or her own research area. This required Joe to distribute the teaching sensitively, to ensure equitable work loads and provide sufficient time for research. He generally managed to achieve this, so his decisions were accepted without dissent. However, on one memorable occasion a replacement had to be found at short notice to teach the 2nd year level course in gastrointestinal physiology. The matter arose at a staff meeting during which Joe asked if anyone would like to volunteer. There were no immediate takers, so Joe decided that he would have to nominate somebody:

JFL: Dr X, since you are not engaged in any research, I think you should take on this responsibility.

Dr X (looking flustered): I’m sorry sir, but I can’t because I don’t know anything about gastrointestinal physiology.

JFL: I expect every member of staff to be able to teach any topic at 2nd year level. I teach four courses, none of which has any relevance to my research. I must insist that you go away and plan how you are going to do it.

Dr X: Well, since you insist, I will. But as you are such an outstanding teacher, perhaps you could advise me on how to proceed.

JFL: Of course. The human GI tract is approximately 32 feet long and you have 8 lectures, so my advice is that you cover 4 feet per lecture.

Joe often relied on his mischievous sense of humour to defuse a potentially difficult situation. The principles that directed our research – innovation together with rational assessment of results – also guided the way physiology was taught. For the large junior classes, Joe initiated debate of the rationale for traditional practical teaching. This resulted in the introduction of a (then) radical audio-tutorial system of teaching, where key concepts were encapsulated in simple lab-based exercises within audio/tape programmes. Comprehension was then tested by a small group of staff and tutors in one-to-one question and answer sessions. A precursor of CAL and FAQ! Joe’s fascination with the use and abuse of statistics resulted in a fruitful collaboration with Richard Cormack, then Professor of Statistics at St Andrews, which led to exercises for the junior classes. A successful textbook, Essentials of Physiology, co-authored with Charles Ingram, Ian Johnston and Bob Pitman, epitomised his approach to teaching, with direct and straightforward narratives illustrated by clear, uncluttered graphs and diagrams.

Joe’s belief in rational decision-making in public-spending policy led him to champion several high-profile campaigns. He was co-founder with Denis Noble, John Mulvey and others of ‘Save British Science’ (SBS), a group that started with ‘crowdfunding’ of a full page letter to The Times, emphasising the considerable successes of British science and protesting the cutting of the Science budget by the then Thatcher government. This was the start of a long campaign (1985-2005), which led to some mitigation of the cuts and, crucially, resulted in the acceptance by successive governments that the benefits of a strong science base greatly outweighed the relatively modest costs. SBS lives on still, in the form of the Campaign for Science and Engineering (CASE), since some of the funding issues that led to its foundation are as relevant today as they were in 1985. Joe also campaigned for improved career prospects and better pay structures for postgraduates and post-docs. His campaigning zeal continued as Chair of the ‘Gas Greed’ campaign that targeted excessive executive pay and poor performance. The Herald noted, ‘As the man to kick-start the campaign, his own research interest on the effects of the stimulant digitalis on the heart, is most appropriate’. Joe deployed half a million shareholder’s votes he had garnered to vote against the Chair of British Gas at the AGM in 2011.

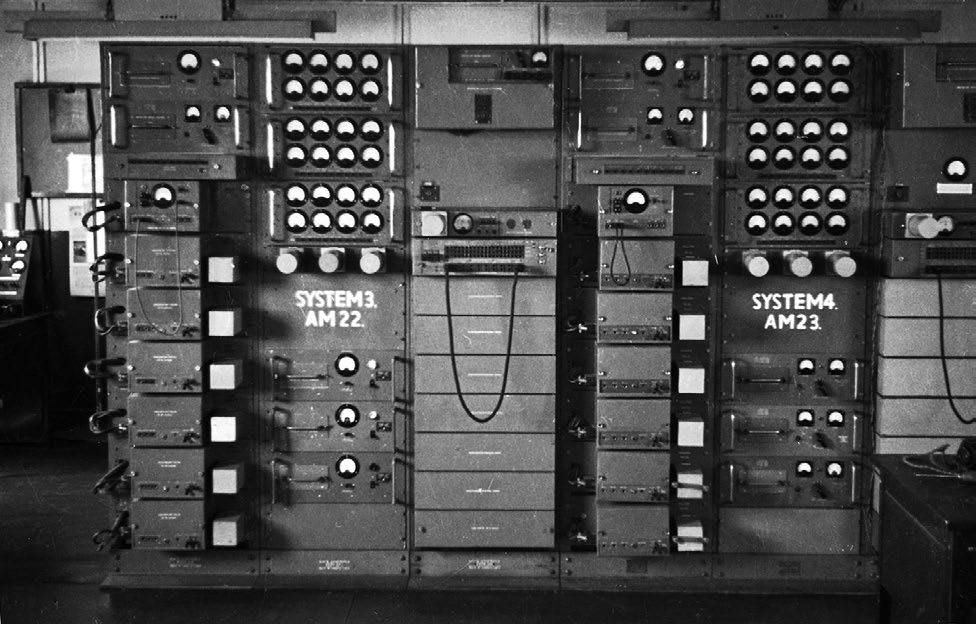

Joe’s well-known love of electronic gadgetry was most likely born at Bletchley Park. First the Sinclair watch, calculator and computer, followed by an Acorn Atom, an Olivetti, a BBC micro, the IBM-PC and then the whole department wired for the Cromemco micro running Cromix. His enthusiasm for the next new computer was unbounded.

Joe was an enthusiastic sailor. He was an accomplished ‘jack of all trades’ in sailing boat building and maintenance at St Andrews. A considerable quantity of teak benching from the refurbishment of the teaching labs in the Bute Medical buildings was ‘upcycled’ for decking and fitting out. He occasionally persuaded (‘press-ganged’, might be a more appropriate term) junior members of staff to serve as crew. On one such trip from St Andrews to the West Coast, two reluctant tars mutinied and jumped ship in Peterhead. On his retirement Joe purchased a 38ft Rival in which he and his family sailed extensively around the UK, Holland and the Bay of Biscay.

Joe Lamb will perhaps best be remembered for raising the national and international profile of research in ‘his’ department. His leadership enabled ‘physiology’ and ‘St Andrews’ to be mentioned together in the same sentence with pride.

Joe is survived by his wife, Bridget, his first wife, Olivia, seven children and eleven grandchildren.

Bis vivit qui bene vivit