Physiology News Magazine

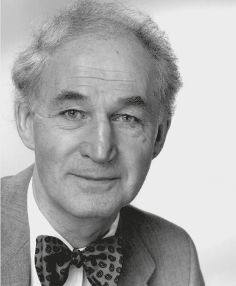

Obituary: William Stanley Peart

1922 – 2019

Membership

Obituary: William Stanley Peart

1922 – 2019

Membership

Written by Peter Sever (Imperial College London).

https://doi.org/10.36866/pn.117.46

Amongst the great British clinician scientists of the twentieth century, Stanley Peart was a giant. His international fame was based on his remarkable scientific research on the autonomic nervous system and the renin-angiotensin system – two systems that play a vital role in the regulation of the circulation and the kidney.

Born in South Shields, County Durham, Peart was a Tynesider. The family moved several times during his childhood and eventually to London. At King’s College School Wimbledon, he excelled in the sciences and entered St Mary’s Hospital Medical School with a scholarship in 1938. A year later, with the outbreak of World War Two he was persuaded to continue his medical studies. By 1943, as a house physician he was advised by his mentor, George Pickering, to spend a short time in the laboratory of Alexander Fleming. This was Peart’s first exposure to research.

At the end of his house jobs, Peart applied for a Medical Research Council (MRC) studentship to work with John Gaddum in Edinburgh in 1946. Gaddum was a shy, gangling figure, awkward in conversation, but a superb mentor. Peart was challenged to work on sympathin, a substance putatively released from sympathetic nerves. There was uncertainty as to whether this was adrenaline or some other mediator. The question was “what actually is released from the nerve endings and how could you measure it?” Peart realised that, rather than the ewe’s liver, then used, a much better experimental model was the perfused spleen, with a rabbit ear as the bioassay the vasoconstrictor effects of the effluent from the spleen. After a series of painstaking experiments, he realised the nature of splenic sympathin could not be adrenaline but was noradrenaline. This result published in The Journal of Physiology in 1949.

By 1952, Pickering was convinced that the future of hypertension research involved the identification of components of the renin-angiotensin aldosterone system (RAAS). The technology to investigate the RAAS was not available in the laboratories at Mary’s and Peart moved his work to the MRC laboratories at Mill Hill. The challenge was to purify and identify the nature of the blood-pressure-raising substance, angiotensin. His early work involved the development of reverse-phase chromatography and the ultimate identification by electrophoresis and spectrophotometry of the amino acid sequence of the decapeptide angiotensin 1. In collaboration with Don Elliott, the resulting classic paper was published in Nature in 1956.

Peart left Mill Hill in 1954 to return to the Medical Unit at St Mary’s, where he was invited to apply for Pickering’s Chair. The youngest applicant by far, he was appointed to the post. The St Mary’s Unit had evolved under Pickering’s influence into the field of hypertension with a focus on how the renin- angiotensin aldosterone system actually worked. The Swiss pharma company Ciba had synthesised angiotensin and this was used for exploratory studies in the laboratory to establish its actions. The interests of the team widened, influenced by Roy Calne, a future internationally renowned transplant surgeon. The team had the experience and ability to start renal transplantation. This was no doubt stimulated by the recent availability of the immunosuppressive agent, azathioprine.

Hypertension in the early 60s was considered the poor relation of cardiology and, in contrast to the enormous national and international cardiology meetings, a small International Hypertension Group of no more than 50 participants held its first meeting in northern Italy. This embryonic hypertension club has now evolved into an International Society with over 4,000 members.

During the 70s and 80s, Peart chaired the Medical Research Society, a society which was probably responsible for the development of academic medicine in Britain. He was appointed to the board of the MRC. He also became a Wellcome Trust trustee. By today’s standards, the Trust was then extremely small with a limited budget of around £1.5 million per year.

After being elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1969 and knighted in 1985 for his contribution to medicine, Peart retired in 1987. This allowed more time for a passion for opera. He loved the blood and thunder operas – those with manifestly aggressive actors and singers – Don Giovanni and Tosca were his favourites. With Italy in mind, a Festschrift (a collection of writings in honour of a scholar) was arranged for him in his favourite place on the banks of Lake Como. It was a memorable occasion attended by over 100 of his former friends and colleagues.

As a family man, Peart owed an enormous amount to his wife, Peggy. He died on 14 March 2019. He was one of the last real professors of medicine – a scientist, a teacher and always a clinician. Those who followed and were fortunate to have worked with him remember the brilliant mind, the charisma, the sense of humour and, perhaps, the bow tie and the red socks.