The heat shock response, our inbuilt protective mechanism against heat injury

Abderrezak Bouchama, King Abdullah International Medical Research Center, King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences, Saudi Arabia

“We had prepared the intensive care unit, the ventilators, and other equipment. As we waited for the Hajj pilgrims at the field hospital, my colleagues asked if I have ever seen heat stroke before? I say no, I’ve never seen heat stroke in my life,” says Abderrezak Bouchama, scientist and clinician. In this interview, he takes us back to the summer of 1986 when he first witnessed heat stroke casualties. Since then, heat stroke has become his life’s work.

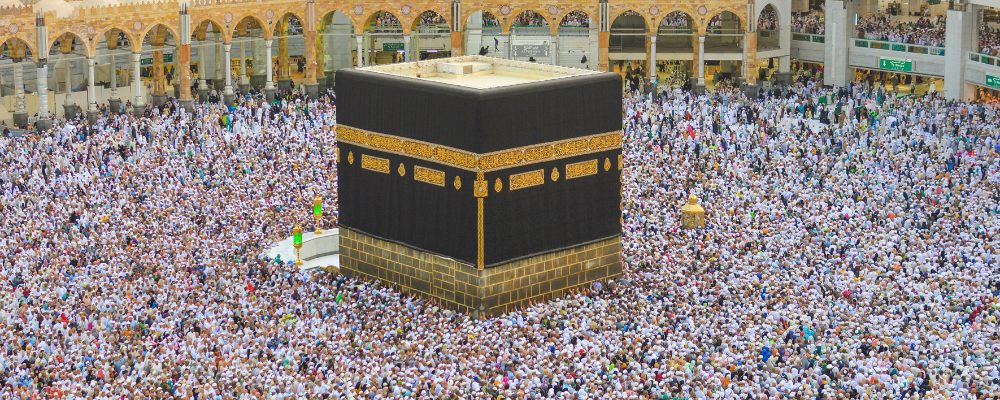

“It looked like a war zone. As if a bomb had exploded in the middle of the crowd. One lying dead, another in need of treatment. People in comas, having seizures, or cardiac arrests,” remembers Abderrezak, telling me about his first experience of heat stroke during the summer of 1986 in Saudi Arabia. Hajj, the annual five-day pilgrimage made by Muslims to the holy city of Mecca, took place in mid-August that year.

Abderrezak arrived in Saudi Arabia in the autumn of 1985. “As a young well-trained doctor coming from the life of Paris, I didn’t know what to expect,” says Abderrezak. He adds, “At the time, my plan was to move to the US. When I saw the advertisement for a consultant in Saudi Arabia, I thought, OK, I’ll go for a few years and then head to US”. As a critical care doctor, he was soon deployed to a field hospital based in Mina one of the pilgrimage holy sites. The pilgrims spend three days there and throw stones at pillars which symbolise the rejection of Satan’s temptation.

Nearly 18,000 patients with heat illness across Hajj field hospitals

“Nearly one million pilgrims arrived in Mina that year; in recent years, the number has exceeded two million. One of the most extreme climates in the world. It’s in the middle of desert, there’s no sand, just rocks. Temperatures can reach up to 50°C as the valley is baked by the sun,” explains Abderrezak.

Early in the morning by around 10am, the hospital was overwhelmed with patients with heat stroke. The pilgrims were crowded in the cooling unit, the ICU, in the corridors, on the floors, and outside.

“I had worked as a critical care doctor for eight years in Paris, so I was used to taking care of severely sick patients. But this was my first time seeing so many patients all sick at the same time.” In August 1986, Abderrezak witnessed the deaths of hundreds of patients with heat stroke in a few days. “It was a turning point for me,” he says. Data later published in The Annals of Saudi Medicine documented the scale of heat illness during the 1985 Hajj, 1000 deaths out of 2,100 cases of heat stroke and reported a total of 15,500 cases of heat exhaustion across Hajj field hospitals.

Out of the nearly one million pilgrims in Mina valley, some developed heat stroke, others mild exhaustion and others did not develop any disease. “We are not equal when we face heat,” states Abderrezak. He explains how some patients quickly recovered and could continue their pilgrimage. While others sadly continued to deteriorate after the doctors had normalised their body temperature. Organ by organ failed until they died. Abderrezak and his colleagues also treated comatose patients who never regained consciousness.

Is there a genetic susceptibility that predisposes some people to heat stroke? Why do people develop permanent neurological damage and the others not? Why do some people recover quickly? “I had more questions than answers about heat stroke.” He adds, “the fundamental biology of heat stroke was not well known”.

During his training in the intensive care units in Paris, the students had learned every cause of hyperthermia: malignant hyperthermia, recreational drug- induced hyperthermia, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, thyroid related hyperthermia, but not heat stroke. “Heat stroke was considered exotic at the time,” states Abderrezak.

A systemic illness

Heat stroke is a life-threatening condition. It is characterised by severe hyperthermia often above 40°C, central nervous system abnormalities (such as delirium, seizures, or coma), and heat exposure or exertion.

“The triad is a simple but deceptive definition,” cautions Abderrezak, “Clinically we use it, but in reality, I’ve seen patients with multi organ dysfunction, from the heart to the lungs, the liver, the kidney and the gut upon arrival.” For the past 40 years, he’s carried out clinical research and developed animal models. Analysing heat stroke from the organ and cell levels to the molecular level to gain understanding of how heat stroke develops.

In the early 1990s, Abderrezak and his colleagues demonstrated that heat stroke is not simply heat toxicity but a systemic inflammatory syndrome — a paradigm shift in understanding the condition. In 2002, Abderrezak and James P. Knochel proposed a new definition of heat stroke in a landmark publication in the New England Journal of Medicine. Explaining that it is hyperthermia associated with a systemic inflammatory response, leading to multi organ injury, in which encephalopathy predominates.

Your body’s heat shield

Environmental heat has become an increasingly consistent threat of climate change. Heat waves are now more frequent, more intense and longer lasting. Exposure to extreme heat can put significant stress on most living species. To protect us against internal damage from heat, humans, and all living species, have a handy shield that is built into our biology. This guard is a heat shock response, also referred to as a heat stress response (HSR), that is activated when you’re in danger.

The HSR is an evolutionary survival programme and a prerequisite for life on Earth. “Without this heat stress response, you cannot survive the planet’s environmental temperature.” Unfortunately, the HSR can fail to prevent heat stroke, despite the shield launching a powerful defence response.

Abderrezak investigated molecular pathways and mechanisms to understand why this critical shield could fail in its protective role against heat damage. He compared heat stroke in patients at the Mina Emergency Hospital, Makkah, with non-heat stroke pilgrims. “The pilgrimage to Makkah is a unique natural experimental world. Over decades, millions of pilgrims have come from hundreds of countries forming a representative cohort. Because of the rituals, all the pilgrims are exposed to the same environmental conditions, wearing the similar clothing, eating the same food and moving around together.”

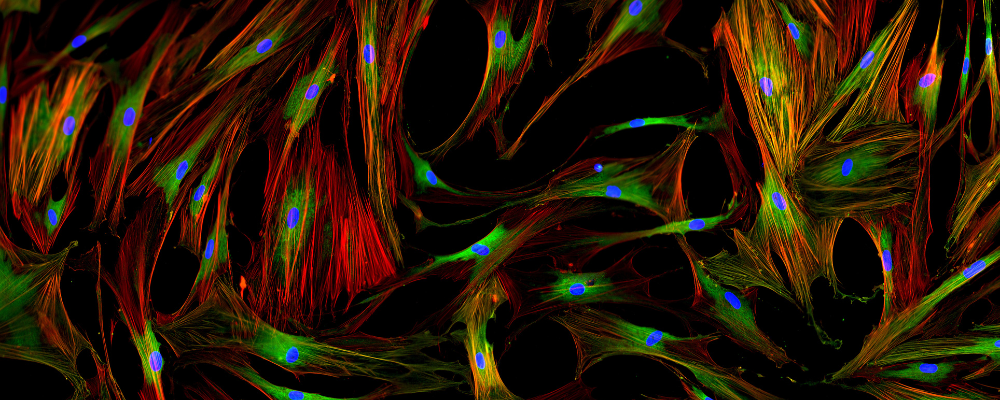

Molecular signatures

He and his colleagues identified a molecular signature of heat stroke, published in The Journal of Physiology. “We showed a huge induction of heat shock proteins in patients with heat stroke. Despite the massive HSR response, it was not enough to protect patients from organ damage from the heat,” states Abderrezak. He adds, “We also saw that another pathway was activated, repair mechanisms for DNA”.

He suggests that we have two defence mechanisms. The first, thermoregulation, allows us to maintain a core body temperature of around 37°C and adapt between different conditions, move from cold to hot. The HSR is the second defence mechanism, engaged when the first is no longer sufficient. The HSR is launched when the body faces thermal regulatory failure and heat starts accumulating.

The repair mechanism reprograms the transcriptome. It halts all business as usual. Cell growth and proliferation stop in favour of a stress response to keep the necessary functions operating and to protect our fundamental structure of life, our DNA, proteins and lipids.

Two possible reasons why the HSR response fails to prevent organ damage from the heat are severe proteotoxic stress in the body and cellular energy failure. The heat shock proteins, which often function as chaperones in the refolding of proteins damaged by heat stress, can’t carry out their role when there is limited energy. They need the energy to bind to and fix the denatured proteins.

During heat stress, our mitochondria “batteries” becomes profoundly impaired. Under normal conditions, they generate approximately 32 ATP in energy for one molecule of glucose, but when the system fails, the body depends on glycolysis, a less efficient pathway that produces about 2 ATP per glucose molecule. “The body behaves like a nuclear reactor,” explains Abderrezak, “it shuts down when faced with extreme heat perhaps to minimise the oxidative stress”.

Cooling mechanisms

Physical cooling is the only current treatment. “Our cooling approach for patients is often archaic and aggressive, and can cause pain and combativeness” says Abderrezak, as he describes immersing heat stroke patient in cold water or covering them in ice when they have a high core body temperature of 42°. “The hypothalamus works via a feed forward control, which triggers the body to shiver to generate heat to counteract the sudden cold and prevent the body temperature from dropping too quickly.”

To avoid this pain and combativeness, he and his colleagues developed an artificial hypothalamus. This biomimetic (a system that can replicate natural processes) cooling system that thermoregulates the body, won them the gold medal at the International Exhibition of Inventions Geneva in 2024. “It works like the hypothalamus, but externally, and is directed by an algorithm via machine learning.” Abderrezak adds, “I envision that it would be a fully automated process. A blanket filled with air or water available in people’s households or public places, like cardiac defibrillator. With a click of a button the blanket would gently cool or warm the person”.

Biomarkers and heat stroke prevention

Along with working on cooling interventions, Abderrezak wants to identify biomarkers for heat stroke so it can be easily diagnosed, like the equivalent of a high sugar level as a marker for diabetes. “Unlike for vascular stroke, a CT scan or MRI shows a heat stroke patient’s brain intact on arrival with no structural damage. You don’t see bleeding, clots or tissue damage.”

Abderrezak’s research revealing molecular changes associated with heat stroke means that he and his colleagues have potential therapeutic targets to work on and his team is developing diagnostic tests. “During collapse of the body’s system, we could boost energy or try to stabilise the mitochondria. This needs a lot of research to find what substances could work.” As he thinks about the possibilities, he adds, “Maybe we could use a small molecule to boost the heat shock response”.

“Most important of all is prevention,” states Abderrezak. “Biomarkers could help us identify people that are more vulnerable to heat stroke and those with a more robust HSR. Then we could work on a therapy to boost the resilience at the molecular level.”

The team are looking into the genetic susceptibility. “We are conducting a genome wide association study to identify gene variants that either increases your susceptibility to heat stroke or increases your resilience,” says Abderrezak. This data would be useful for pilgrims in the desert of Makkah, as well as people exercising in the heat. “You would know whether your genome made you more resilient or more vulnerable, so would need more protection from the heat,” explains Abderrezak.

Our body’s own heat shield might not be enough to protect us from heat stroke, but the dedication of Abderrezak gets us closer to novel diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to protect us from the heat. He says cheerily, “maybe in a few years we will have the answers for a targeted precise public health strategy for heat stroke”.

Read the full research article published in The Journal of Physiology, ‘Whole genome transcriptomic reveals heat stroke molecular signatures in humans’.