Physiologist, or educator? Learning to wear both hats

Matthew J. Mason

Department of Physiology, Development & Neuroscience

University of Cambridge, UK

“Initially, learning the language of education proved challenging to me as a scientist. How should we be ‘reflective’ in our teaching, for example? I wanted something concrete to work with, and found what I was looking for in a classic work by American philosopher John Dewey.”

I feel very honoured to have been awarded the 2025 Otto Hutter Teaching Prize by The Physiological Society, not least because I was nominated for this by one of my former students (to whom I am deeply indebted!). It was a pleasure to give the associated lecture at the ‘Challenges and Solutions for Physiology Education’ meeting in Bristol in April, and to have that opportunity to celebrate the life and work of Professor Hutter, who did so much to advance the educational goals of The Physiological Society.

Physiologist?

Starting as a veterinary student at the University of Cambridge, I soon realised that my interests lay more in the internal workings of unusual animals than in treating dogs and cats. I changed direction, completing a PhD with Adrian Friday on the structure and function of the mammalian middle ear before moving to UCLA for a postdoc with Peter Narins in the Department of Physiological Science, where I used laser vibrometry to study frog hearing. During this time, my focus was almost entirely on research.

Following my return to Cambridge, I eventually became the University Physiologist and Professor of Comparative Physiology, and the Robert Comline Fellow in Physiology at St Catharine’s College. My unique title of ‘University Physiologist’ might seem odd given that there are many physiologists in Cambridge, but it reflects my central role in teaching this subject to our medical, veterinary and natural science students. Although I continue to research the weird and wonderful, from armadillos to zokors, this has to fit into a very busy timetable.

For over twenty years now, I have been running practical classes, lecturing, supervising and examining students. I get a real buzz out of helping them engage with tricky physiological concepts, especially when you see their eyes light up as they finally catch on. From this point of view, my transition into a (largely) teaching role was rewarding from the start, but given that I was now spending most of my time on this, was I really still a physiologist, or should I consider myself an educator?

Or educator?

At first, I felt uncomfortable being seen as an ‘educator’, a term which I associated more with academic pedagogy than with scientific expertise. I was sceptical of the value of academic pedagogy. What would educationalists know about how to teach equilibrium potentials to medical students?

Katharine Hubbard, a colleague from another department, had recognised the importance of educational research long before me. In response to my dark mutterings on the subject, Katharine asked if I had ever really looked into it. I was embarrassed to admit that I had not, and to rectify this I enrolled in my university’s outstanding Postgraduate Certificate in Teaching & Learning in Higher Education course.

Initially, learning the language of education proved challenging to me as a scientist. How should we be ‘reflective’ in our teaching, for example? I wanted something concrete to work with, and found what I was looking for in a classic work by American philosopher John Dewey. Dewey’s (1933) concept of reflective thinking essentially involved identifying a problem, coming up with an idea, implementing it and considering the result, the process being iterative if the problem is not resolved. Like testing a hypothesis, then – that computes!

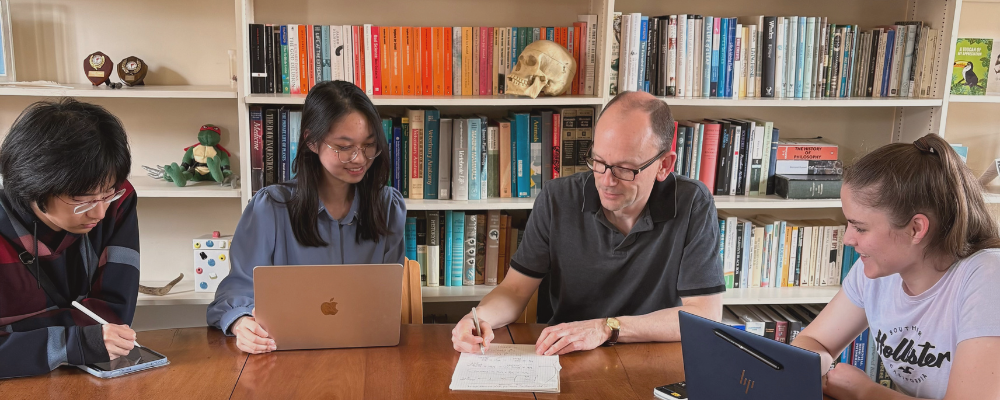

I gradually began to think more deeply about my teaching, learned about new approaches and developed the confidence to try some of them out. I changed my digestion lectures to a ‘flipped classroom’ format, to engage students more actively (Mason & Gayton, 2022). At first, my audience used ‘clickers’ to vote for multiple-choice answers. Reflecting further on this (there’s that word), I realised that I wanted to move away from that kind of thinking and get the students to discuss principles and implications instead. The clickers disappeared and the nature of the questions evolved.

I came to see the importance of the informal contact between academics and students within a teaching laboratory, in breaking down barriers and initiating scientific conversations (Mason & Jooganah, 2024). However, the needs of undergraduates and their ways of working are rapidly changing, and I began to accept that we need to adapt our teaching accordingly. My former student Cong Cong Bo, a gifted animator, worked with me to produce a YouTube channel, www.hippomedics.com, to help convey the basic physiological principles that can be lost in the galaxy of tiny details, while the online, interactive essay-writing tutorial created by Alex Swainson and Frankie MacMillan at the University of Bristol, which I learned about at a Physiological Society meeting, is now proving invaluable to freshers in Cambridge too.

In the late 1960s, Otto Hutter ran courses for school teachers, to help them keep up with physiological advances. The educational mission of The Physiological Society grew from there and The Society now hosts an online Training Hub, devoted to helping younger academics with their career development. I was delighted to have had the chance to support this endeavour, which continues Hutter’s legacy, through developing video resources aimed at new physiology lecturers who are just starting to teach (Mason, 2024).

Wearing both hats

I now recognise that there is much to be learned from educational research. However, there is much that we can give back too, from our perspective as trained scientists. When the benefits of a new way of teaching are touted, we should determine whether a different approach would have worked better, through a controlled experiment. When low-performing students improve following an intervention, we should be asking if this goes beyond regression to the mean. When an exam change closes an awarding gap, we should consider whether this was simply because the mean mark increased. We can be educators but we can be physiologists too, whether or not we continue to be active in scientific research. We should be comfortable wearing both hats.

References

Dewey J. (1933) How We Think, new edition. Boston: D.C. Heath and Company.

Mason, MJ. (2024) Video resources for new physiology lecturers. Physiology News 133: 38-39

Mason, MJ. & Gayton, A.M. (2022) Active learning in flipped classroom and tutorials: complementary or redundant? International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning 16: 1-11.

Mason, MJ. & Jooganah, K. (2024) Online versus live practicals: what were physiology students missing during the pandemic? In: From Lab to Laptop: Case Studies in Teaching Practical Courses Online. Betts, T. & Oprandi, P. (eds). University of Sussex: Open Press.