A framework to overcome students' coding anxieties

By Nadia L Cerminara

School of Physiology, Pharmacology and Neuroscience, University of Bristol, UK

Nadia and colleagues at the University of Bristol designed a series of R workshops to help first- and second-year undergraduates overcome coding anxieties and improve their chances when applying for research or industry positions. Nadia shares how she and the Bristol team structured the workshops to boost students’ confidence.

Why coding matters in the life sciences

Whether investigating neuronal firing patterns, monitoring glucose continuously, or exploring genomic trends, laboratories today generate large volumes of data that demand computational tools for meaningful insights. Therefore, life sciences graduates are required to develop the ability to handle, analyse, and interpret large datasets. Coding, once perceived as the domain of a computer scientist, has become an increasingly in-demand skill for physiology and related fields in order to deal with big data. Beyond facilitating data analysis, coding promotes problem-solving, critical thinking, and collaborative learning.

Yet many life sciences curricula lack structured opportunities to introduce coding, leaving life science graduates at a disadvantage when applying for research or industry positions. Recognising this gap, colleagues and I at the University of Bristol designed a series of R workshops (R is a free, open-source environment for statistical computing and graphics) to help first- and second-year undergraduates overcome coding anxieties in a supportive, scaffolded framework.

Barriers to introducing coding in life sciences degrees

Despite clear benefits, integrating coding into existing courses is not without challenges. From the student perspective, encounters with coding often evoke apprehension around a worry that coding requires advanced mathematics or specialised training. Although today’s students are often labelled ‘digital natives’ due to growing up with technology, we have found that digital literacy is surprisingly low. First-year students in particular frequently struggle with computer skills such as spreadsheet manipulation, a foundational skill needed before coding. With heavy course demands (labs, lectures, assessments), coding sessions are viewed as optional “add-ons”; students prioritise topics they perceive as more directly related to their degree.

Staff face similar hurdles: without a coding background, many feel ill-equipped to teach programming and struggle to find time for self-paced training amid teaching and research duties. With packed modules, carving out time for coding essentials without displacing core physiology content is challenging. Moreover, novice coders often need one-to-one help with syntax errors or file issues, placing pressure on staff resources.

Collectively, these factors create a pervasive “fear” of coding where staff worry about the workload and technical hurdles and students feel anxious about trying something unfamiliar. To this, the Bristol team implemented a scaffolded approach to coding, gradually building student independence and competence through sequenced workshops.

A scaffolding model for R coding

To this end, we developed three linked workshops:

- Year 1, Semester 2: Students log into RStudio via Posit Cloud, eliminating installation issues and ensuring a consistent environment across Windows and macOS. Rather than starting from a blank script, each student receives a script with prewritten code importing a simple dataset from a practical they performed – examining how posture and physical activity affect the renal response following water ingestion. Working through this code, students learn to navigate RStudio, run individual lines, and interpret console messages. The focus is on familiarisation: seeing that R commands correspond to concrete outcomes and produce basic graphs and statistics.

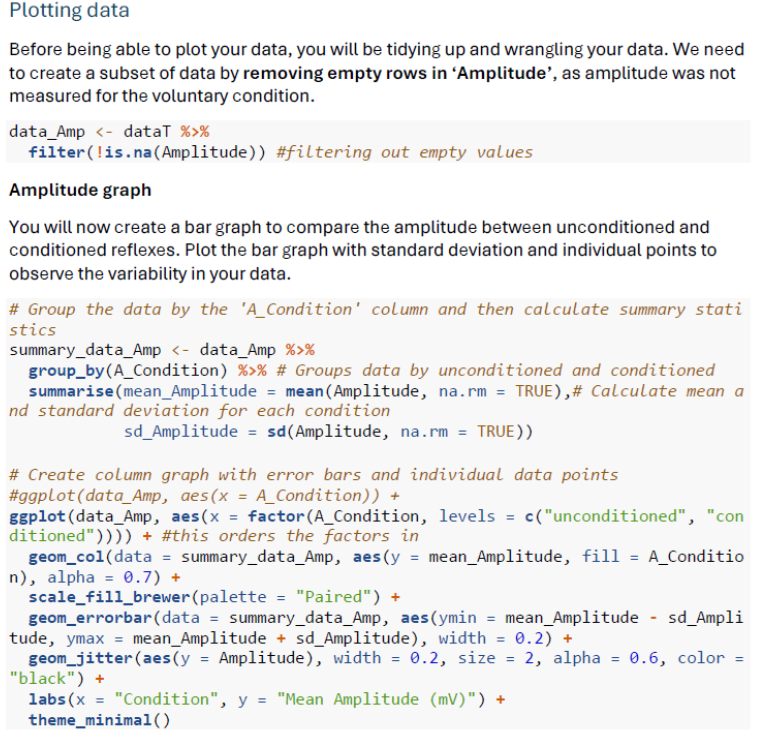

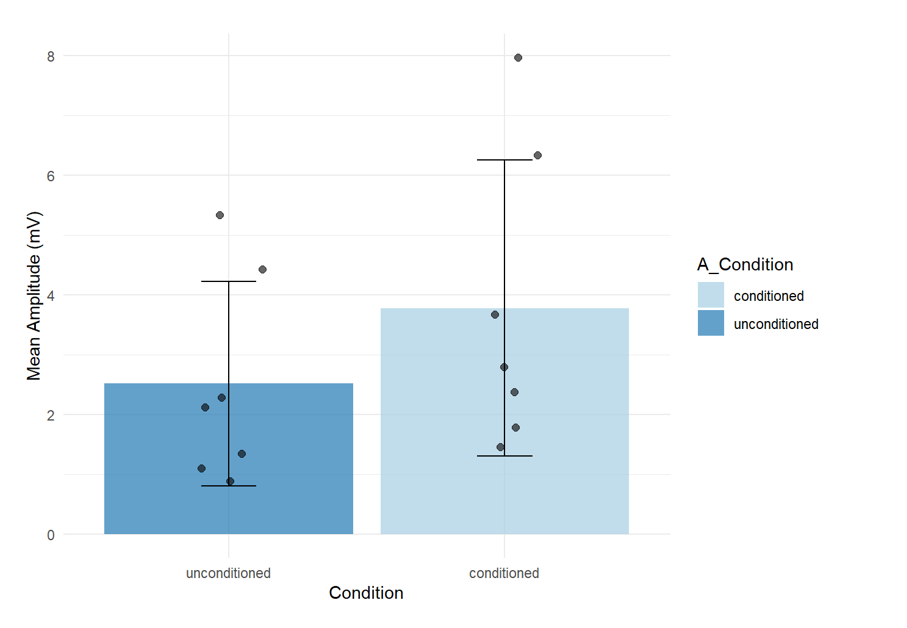

- Year 2, Semester 1: Again using a familiar dataset (from a tendon reflex practical), students work with an RMarkdown document containing prewritten code interspersed with explanatory text. In this session the students learnt how to alter the spreadsheets into the format used by R.

- Year 2, Semester 2: Students adapt small sections of code within an RMarkdown document. They import, clean, and combine multiple datasets; create publication-quality figures (e.g., box plots or a scatter plot with a regression line); and perform summary statistics and tests. Students were encouraged to modify simple parameters (e.g., changing plot labels or adjusting an axis range). They also began to appreciate how code can automate repetitive tasks.

By structuring the workshops so that initial tasks required no coding and gradually building to editing prewritten scripts, we observed a marked decline in student anxiety. Early successes such as “I ran that code and got a graph!” became confidence-boosting milestones. As a result, even students who initially declared, “I’m not a coding person,” reported feeling more comfortable venturing into unscripted tasks.

Key lessons learnt

Early workshops taught us that even minor ambiguities, such as where to save a file or how to navigate to a specific directory, can derail student confidence. Providing screenshots, bullet-point instructions for Windows vs. Mac, and anticipating common pitfalls (e.g., CSV files formatted differently on macOS) proved essential. When students could complete the “setup” phase without frustration, they approached coding more positively.

Instead of treating coding as an “extra”, each workshop was explicitly tied to physiological data familiar to students. Whether analysing reflex responses or renal responses from a water load, students saw that R was not an abstract skill but a powerful tool to help understand their data. This reinforced motivation, and students recognised that coding directly enhanced their ability to interpret experimental results.

The RStudio/RMarkdown ecosystem demystifies coding by interweaving narrative text, code chunks, and output in a single document. Students appreciated executing one block of code at a time, viewing results immediately, and reading plain-English explanations alongside. By exporting their work as HTML or PDF reports, they illustrated how coding fosters reproducibility, an important principle in scientific research often underappreciated in traditional “point-and-click” analyses used by programmes such as Excel, Prism or SPSS.

AI tools can provide supplemental support

In later iterations, we now ask students to experiment with ChatGPT (and other AI-specific tools like R Tutor) by crafting prompts to explain lines of R code or suggest debugging strategies. We introduced a “model prompt” (e.g., “Explain what this line of R code does”), encouraging students to critically evaluate AI output rather than accepting it blindly. While generative AI is no substitute for conceptual understanding, it served as an on-demand “second opinion” that some students found reassuring when immediate instructor help was not available.

Looking ahead: Expanding and embedding coding

While the three workshops have garnered positive feedback, there is room for improvement. Ideally, R-based modules would appear across multiple courses (biostatistics, experimental neuroscience, systems physiology) so that coding remains “alive” in students’ minds, preventing skill decay. To this end, we now teach statistics in Years 2 and 3 in R, and we are developing enhanced asynchronous self-paced tutorials and curated “error dictionaries” (lists of common R error messages with corrective steps) to empower independent practice.

As ChatGPT-style tools evolve, guiding students on ethical and effective use of generative AI will be crucial. We plan to introduce bite-sized discussions on AI-generated code limitations, emphasising that tools like ChatGPT offer suggestions but must be validated by the programmer.

Our overarching aim is that, by graduation, most life sciences students at Bristol feel at ease and confident enough to code their own analyses, familiar with reproducible research best practices, and aware of how coding bolsters employability in biotechnology, academia, pharmaceuticals, and beyond.