Exploring undergraduate student perceptions of ‘engagement behaviours’

By Dr Oli Steele (Clinical Neuroscience, BSMS), Dr Alex Stuart-Kelly (Life Sciences, University of Sussex), Dr Elaney Youssef (Medical Education, BSMS) and Shalini Ram (4th Year Undergraduate, BSMS)

From left to right: Dr Oli Steele, Dr Alex Stuart-Kelly, Dr Elaney Youssef, Shalini Ram

A student-led educational research project

As physiology educators, engaging students actively in large group settings (e.g., lectures) in STEM is both a key challenge and rewarding goal. Through a student-led mixed-methods project, we explored undergraduate student perceptions of ‘engagement behaviours’ and approaches in large group teaching of life sciences and medicine programmes at the universities of Brighton and Sussex.

Through a combination of surveys and focus groups led by our project student, two key observations were corroborated: 1) Despite low self-perceived levels of engagement in large classes, students reported improved engagement with the use of multiple active learning approaches into lectures, particularly problem solving, group discussions, and gamified quiz-based systems; 2) Students particularly reported that ‘low-stakes’ individualistic and collaborative activities (e.g., through use of learning technologies) were rewarding and reduced anxiety-load in large class settings.

Together, this project reflects a successful example of student-led educational research and co-creation, which will feed directly into curriculum reform. We aim to use this to inform best practices in physiology education to meet the evolving needs of our student body, whilst in the challenging higher education landscape in STEM facing growing class sizes.

What inspired the idea behind the student-led project?

Alex, Elaney and Oli are all actively involved in module and phase leadership across medicine and life sciences, and regularly deliver a high volume of large-group teaching sessions. Shalini has first-hand (and considerably more recent) experience of large group teaching at UK HE institutes being a current undergraduate student. As we all have, Shalini has had to endure lectures that seemingly do their best to prevent students from actively engaging with the material.

Collectively, we were motivated to understand what the barriers were to engagement in large group teaching in our subject areas, what teaching methods students preferred in relation to engaging, and whether practical guidance could be developed from these insights. To ensure that the direction the research took and the insight gained from the students was as authentic as possible, it was important to remove as much bias introduced from our viewpoint as staff as possible. We felt strongly that this was an ideal project to be student led for these reasons.

Favoured teaching methods by life sciences students

We’ll focus here on the insights Shalini gained from the life sciences cohort as their report focussed predominantly on this group. We will then look to build a larger paper that will discuss these themes in more detail and compare the responses of life sciences students to an equivalent cohort of medicine students also recruited as part of this study.

Shalini managed a monumental effort in recruiting 111 students from 1st and 2nd year life sciences courses at the University of Sussex to answer our surveys targeting engagement behaviours and engaging teaching methods. Intriguingly, students self-rated ‘participation’ behaviours as their least characteristic component of engagement, relative to study ‘skills’, students ‘affective’ relation to the study material, and their perception of class ‘performance’ (Handelsman, 2005).

Upon further analysis of the questions targeting the ‘participation’ component, the data showed that students were significantly less engaged with ‘individualistic’ participation scores (e.g. hand-raising, answering questions, directly seeking lecturer feedback) compared to social scores (e.g. helping other students, having in-class discussions).

Further, when surveying which teaching methods students found most engaging, students felt that teaching methods which introduced clear structure to their lectures, quizzes and polls, problem solving, and other active learning approaches had a strong positive effect on their engagement within large group teaching. Moreover, we found minimal differences in these measures between life science degree programmes and years, suggesting that these engagement behaviours may be conserved across a wide cohort.

Understanding the student experiencing on collaborative vs individualistic learning

Informed by these insights, Shalini then developed guiding questions for, and led a focus group to understand the lived experience of these students. Here, the students strongly resonated with the idea of preferring collaborative learning strategies over individualistic with quotes suggesting that students found ‘putting their hand up or directly asking questions stressful and intimidating’ and spoke positively about tools that enabled low-stakes individualistic engagement such as Slido, Poll Everywhere, Padlet and Mentimeter.

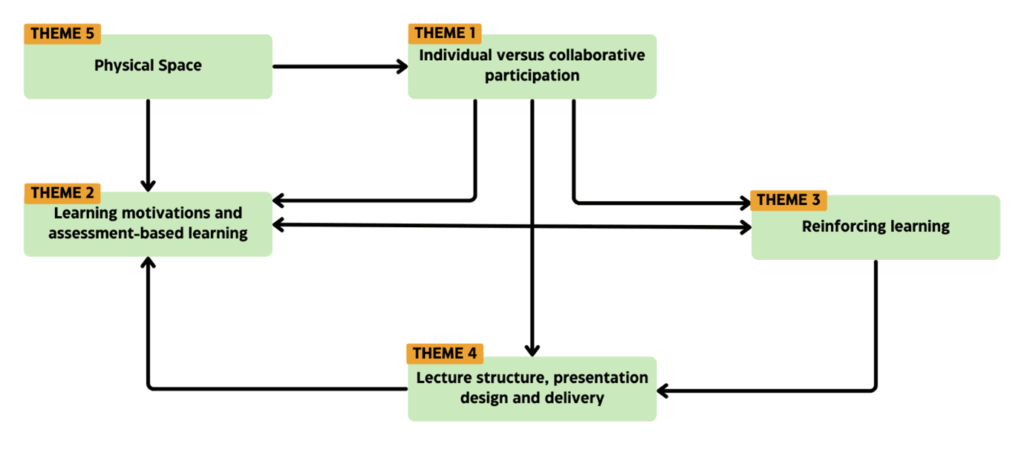

Shalini used the data and focus group discussion to develop a model of factors influencing engagement practices in large group teaching (see Fig. 1) in which five common themes emerged. Theme 1 relates to the individualistic vs collaborative participation already discussed, whereby students value low-stakes opportunities to contribute actively in class, particularly when scaffolded into group settings.

This feeds into Themes 2 (learning motivations and assessment-based learning), 3 (reinforcing learning) and 4 (lecture structure, presentation, design and delivery), which can be supported by incorporating assessment-aligned active learning techniques, in a repeatable manner in and out of class, and are clearly structured within the lecture narrative. There is of course interplay between these co-dependent themes. Finally, Theme 5 (physical space) can complicate large-group teaching, and needs to be critically considered for the logistics of supporting an active classroom. These constraints therefore also have some influence on Themes 1 and 2.

What did you find are the barriers to student engagement?

During large group teaching, Shalini identified that students are less engaged with activities they perceive to have lower value. Students felt that developing transferrable skills should be integrated into their curriculum.

Students also shared that they are resistant towards participating in individualistic activities, such as hand raising as they can create a stressful and judgemental atmosphere.

Collaborative activities which students enjoy and feel more engaged with can be less accessible in the space provided during large group teaching

Logistically, lectures are typically lengthy and consecutive due to timetabling constraints. Students therefore are required to be engaged with the same format for longer periods of time. Students felt these teaching sessions often lacked structure and order.

Related to this, was slide use and lecturer performance. Overwhelming slide density and unstructured layout can deter students from engaging with the material more deeply. Students felt they engaged poorly with lecturers who read text from their slides without clearly incorporating it into a narrative or having a performative element to the lecture.

Do you think any of the outcomes were different because it was a student-led project?

With Shalini as the leader of the project, active member of the research group, and a student themselves, they can appreciate both sides of the picture more clearly than the supervisory team. Particularly, as indicated earlier, it is hoped that the insight gained from this study is less influenced by the unconscious bias that the supervisory team have as lecturers. Whether that bias is to fit the positive feedback to a particular teaching method they champion, or downplay feedback that suggest improvement and innovation may be required.

Further, as Shalini also led the focus groups with a member of staff from the opposite institution present, it was felt that students could speak more freely, avoiding the demand characteristics of discussing in the presence of a lecturer they know.

Do you have any tips for large group teaching?

We have a few recommendations:

- As having clear structure, narrative, and ‘revisability’ is essential, we recommend clearly breaking down your lecture into digestible high-yield sections.

- Adding to this, break these sections up with active learning techniques e.g., methods of testing a student’s knowledge that is relevant to their assessment style; inclusion of media, case studies etc.

- Clearly justifying to students the value of engaging with active learning approaches to get student buy in, while also providing opportunities for students to engage through different modalities (e.g., individually, online, collaboratively as a small group, ways to still engage in the discussion out of class etc.)

- Focus on a central, key message. As academics, we tend to underestimate the cognitive load that we give our students with the volume of content delivered. If content can be clearly related back to a central principle or theme, this can make engagement more sustainable for the students.

We are actively working on developing resources and examples of this to share with the Physiological Society more widely in due course.

Any tips for anyone looking to run a student-led project?

Only that you should do it more often. Shalini’s insight was refreshing and invaluable in equal measure, and importantly different to that of supervisors long past their time as students!