Tailoring active learning to meet student needs

By Dr Clare Tweedy and Dr Alexandra Holmes

School of Biomedical Sciences, University of Leeds, UK

Clare Tweedy (right) and Alexandra Holmes (left) are both Teaching & Scholarship lecturers within the School of Biomedical Sciences at the University of Leeds (in Neuroscience and Pharmacology, respectively). They are passionate about active learning and jointly lead a University-wide Active and Experiential Learning research incubator through the Leeds Institute for Teaching Excellence (LITE).

The idea for our workshop at this year’s ‘Challenges and Solutions for Physiology Education’ meeting stemmed from a shared frustration: active learning is often treated as a checkbox activity, added under pressure to make teaching interactive or innovative. As a result, active learning is often the first to be left by the wayside when challenges arise, like larger cohort sizes or constraints to time and physical space. We wanted to challenge that mindset. Our workshop aimed to show how active learning can be implemented, at scale, in physiology education using a design-thinking approach. We advocate for this approach to ensure that active learning is not just included for the sake of it but is purposeful and tailored to both learning outcomes and student needs.

The design-thinking approach to planning active learning

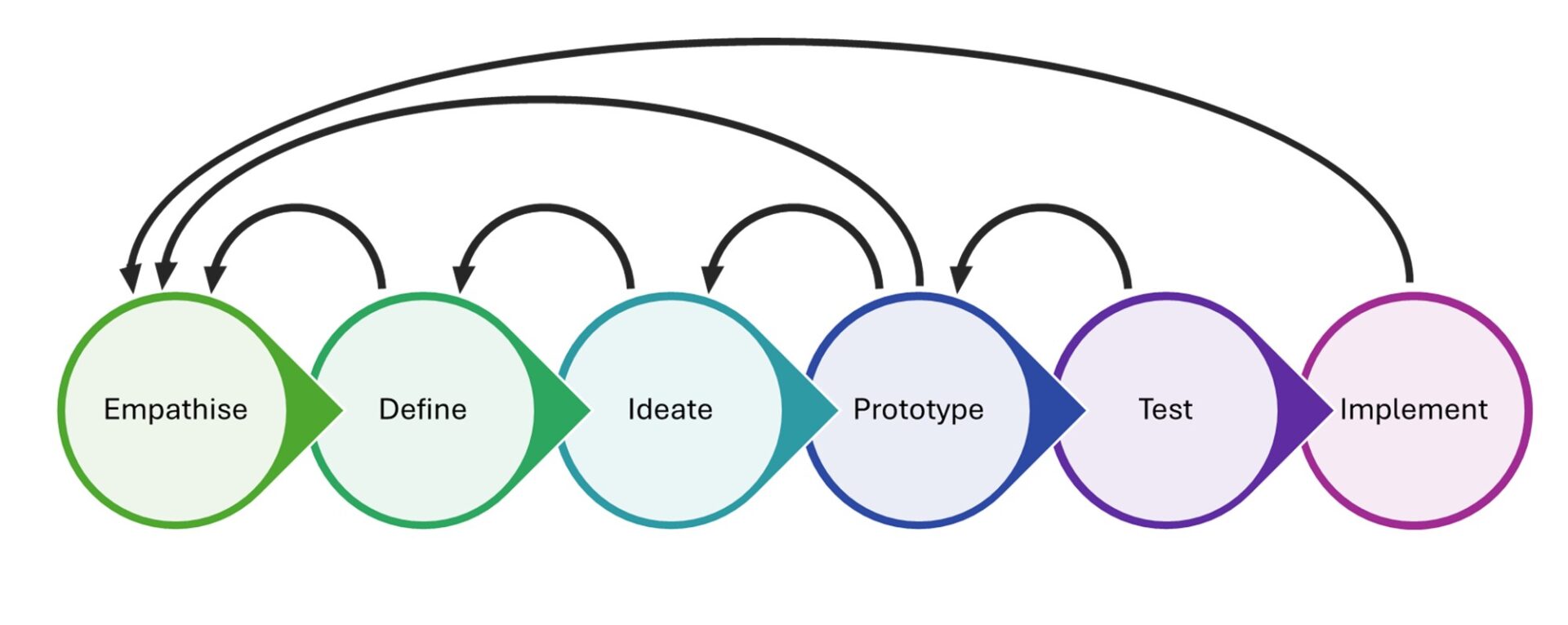

Design-thinking is an iterative process that emphasises empathy with users – in this case, students and educators. The process (see Fig. 1) is non-linear and can begin at any stage, offering a powerful framework for planning active learning. By understanding your learners and their needs, you can design activities that are focused, inclusive, and relevant to your learning outcomes. The empathy stage is therefore crucial to the whole process. Our workshop took participants through the first 3 stages: empathise, define, and ideate.

STEPS 1 & 2: EMPATHISE AND DEFINE

Why is active learning so important for physiology education?

It’s well-documented that active learning has benefits for both learners and educators, from increased motivation and engagement, to developing a deeper understanding of content (as reviewed by Martinez and Gomez, 2025). So, we won’t wax lyrical about why active learning is crucial in higher education, but why is it particularly important in physiology education?

For us, it comes down to the very nature of physiology. Faced with such vast amounts of information, you can understand why physiology students quickly feel overwhelmed. Many therefore advocate for the teaching of “core concepts” in physiology (an approach reviewed by Schaefer and Michael, 2024). Active learning offers an opportunity for students to apply their understanding of core concepts to new scenarios. It encourages appreciation of the complexity of life, integration of systems, and the prediction of outcomes through data interpretation and critical thinking. Active learning asks students to be engaged in their learning, and one of the easiest ways to do this is by framing theory in real-world examples. At its core, physiology is the science of life – you can’t get more ‘real-world’ than this.

So, what’s the problem? Why doesn’t everyone do active learning?

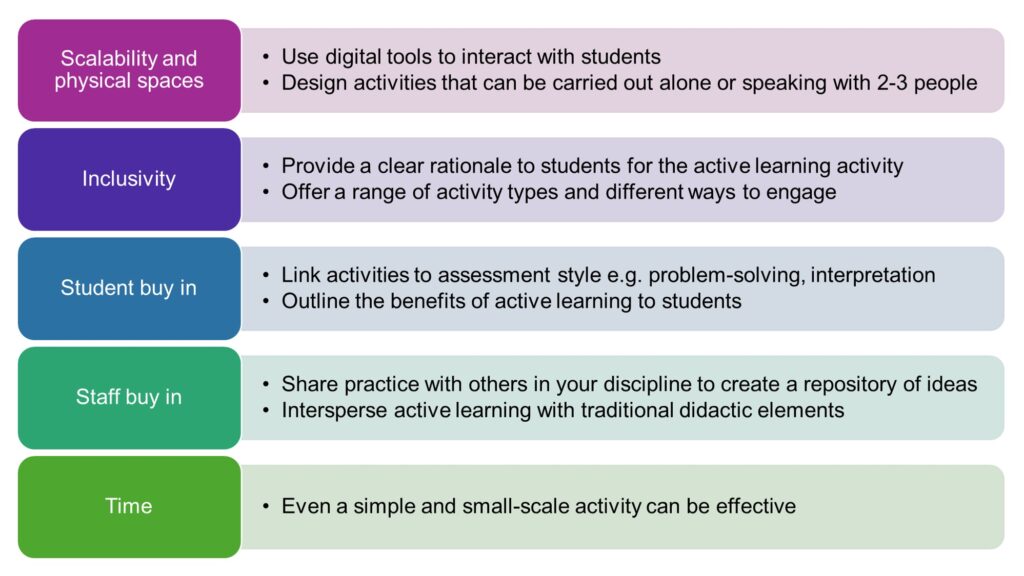

In all the iterations of our workshop, no matter which discipline background the participants are from, we see them reflect on the same barriers: scalability and physical spaces, inclusivity, student and staff buy in, and time. These challenges are universal. What surprised us most from running these workshops was how so many of the challenges are out of the educator’s control: securing the right room for the session, finding time to design, adapting to larger cohort sizes, and issues with technology. Acknowledging these challenges and building them into the design of sessions goes a long way in the next stage of the design-thinking process.

STEP 3: IDEATE

How might we… facilitate active learning with these considerations?

“How might we…” statements are a key tool at this stage: “how might we create an active learning activity that works in a lecture theatre?”, “how might we ensure everyone is able to participate?”, “how might we adapt to changing technology?”.

Sometimes the best answer is going back to basics. Although the words “active learning” may conjure to mind a loud and busy teaching space where everyone is engaged and involved – one key point we took from our workshop is that active learning can also be entirely introspective. Even simple activities can be effective – like asking students to reflect on their skills, or which concepts they find most challenging. Blending these quieter pauses with interactive tasks can also help to reach a wider range of learners.

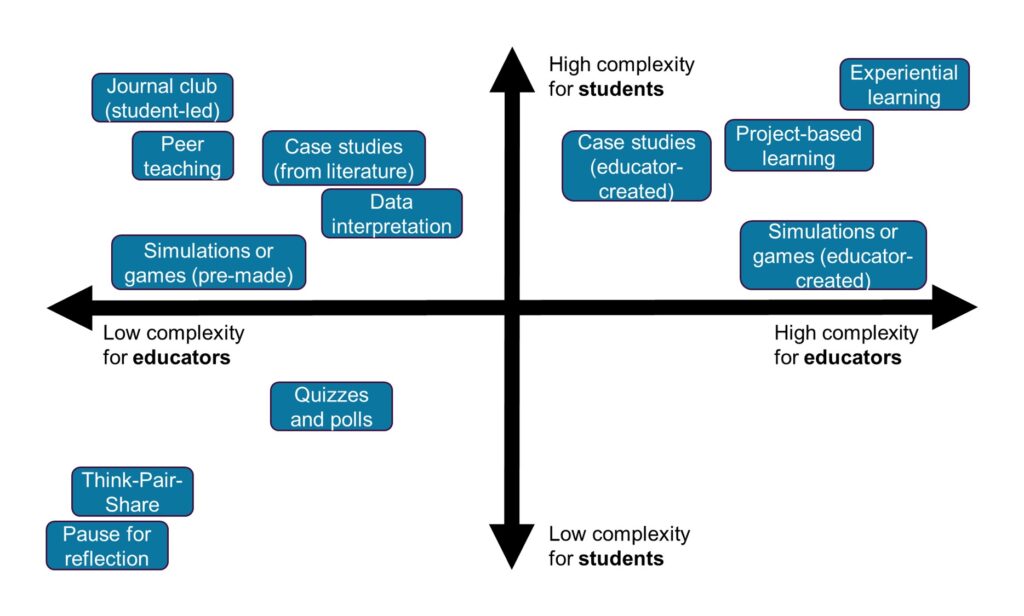

Going back to basics also doesn’t mean simplifying learning. Some activities – like polls and think-pair-share are simple to design and run. Others require more staff preparation but offer substantial learning gains like experiential learning, projects, or educator-created simulations. Activities like student-led journal clubs, data interpretation, and evaluation of clinical case reports strike a balance: minimal prep but complex for learners. Often it is a trade-off – what are the students going to gain from the activity and at what ‘cost’ (staff time for preparation, delivery difficulty, etc.). We have summarised some of these ideas in Figure 2.

STEPS 4 & 5: PROTOTYPE AND TEST

If at this point, you’re still drawing a blank or need more inspiration, it’s always appropriate to see what people have done previously. In our workshop, we shared some of the adaptations we have tried in our own practice at the University of Leeds (summarised in Fig. 3) and would recommend books such as “100 Ideas for Active Learning” from the Active Learning Network (edited by Betts and Oprandi, 2022).

Once you’ve designed your active learning activity, it’s time to test it. It’s important at this stage to set out what ‘success’ looks like for you. Did it help students meet the learning outcomes? Did they find the session engaging and dare we say, ‘fun’? Like any experiment, it may not work perfectly the first time. If it doesn’t, revisit the ‘empathise’ or ‘ideate’ stages to refine your approach. And yes, sometimes that means completely re-designing the activity.

Whether your design works first time or takes several iterations, it’s important to disseminate what worked and what didn’t. This doesn’t only mean conference presentations and papers – it could be as simple as sharing practice with colleagues in your department. Designing active learning is an iterative process but we recommend it also be a highly collaborative one.

Our final recommendations for designing effective active learning activities

- Ensure activities clearly align to learning outcomes.

- Make the link to assessment clear for students.

- Explain the rationale to students – why this activity, why now?

- You don’t have to change everything at once, and you don’t have to be carrying out complex experiential learning in every session you teach.

- Share practice with colleagues for ready-made discipline-specific ideas.

References

Martinez ME & Gomez V. (2025). Active Learning Strategies: A Mini Review of Evidence-Based Approaches. Acta Pedagogia Asiana, 4(1), 43–54. https://doi.org/10.53623/apga.v4i1.555

Betts T & Oprandi P. (Eds.). (2022). 100 Ideas for Active Learning. OpenPress University of Sussex. https://doi.org/10.20919/OPXR1032

Schaefer JE and Michael J. (2024) Core concepts: views from physiology and neuroscience. Front. Educ. 9:1470040. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1470040