The adaptable, underappreciated and inexpensive animal model

By Ann M Rajnicek

Institute of Medical Sciences, School of Medicine, Medical Sciences and Nutrition, University of Aberdeen, UK

“A highly attractive aspect of this practical is that it is very inexpensive to run, even for large classes. In addition to a planaria colony and your selected drug, it only requires basic laboratory tubes and dishes (or cheap kitchen storage tubs), pipettes, gloves, filter paper, ice, scalpels, and artificial pond water (or some brands of mineral water).”

Given increasing budgetary challenges and the need for hands-on undergraduate practicals how can we deliver relevant and engaging lessons that are cost effective and adaptable?

Many animal models used in physiology teaching are expensive, especially for large classes, and many models are less attractive when the NC3R principles of replacement, reduction and refinement are considered. I’ve approached these collective challenges by using planaria flatworms (Dugesia japonica and Schmidtea mediterranea), an underappreciated, inexpensive animal model consistent with NC3R ideals.

What are planaria?

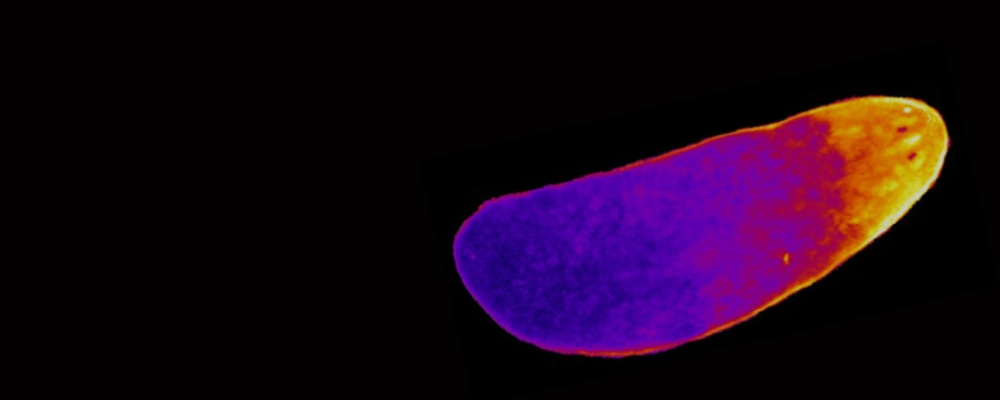

Planaria are small (< 1 cm) nonparasitic, free-living flatworms with impressive anatomical complexity. They have organ systems of interest to physiologists: nervous system (brain, paired ventral nerve cords, sensory neurons, photoreceptors), primitive excretory system (protonephridia), an immune system, tri-lobed gut, muscles, ion transporting epithelia, and (in sexual strains) a reproductive system. Respiratory and cardiac systems aside, there’s something for nearly all physiologists.

How are they relevant to physiology?

Ion transport by frog skin and the consequent transepithelial voltage gradient is a standard lesson in physiology. What is not widely appreciated is that this occurs in planaria skin too. Undergraduate students have worked with me on focussed (9 week) laboratory honours projects to measure the transepithelial voltage gradient across the outer epithelium of planaria using classical electrophysiological techniques. Ion substitution and pharmacology experiments further revealed key components of this ‘skin battery’. Since planarian skin properties aren’t fully understood this is an interesting system that invites continued comparison with the classical frog skin model.

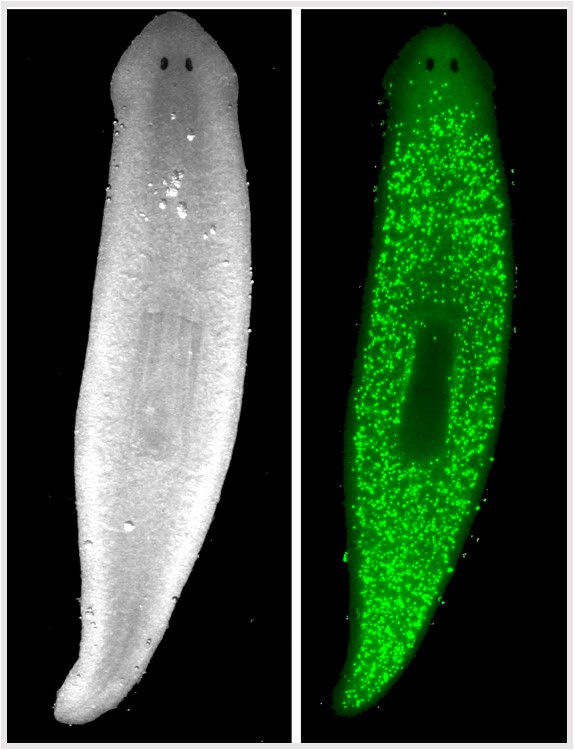

Transepithelial potential measurements also revealed a head-to-tail gradient inside the worm’s tissues (tail is relatively positive). Skin cells at the head region and tail region also display a membrane potential gradient, with head cells depolarised relative to tail. Other honours projects explored how this membrane potential gradient is linked to regulation of planaria stem cell biology, covering topics of membrane potential, the mechanism and limitations of membrane potential reporter dyes, quantitative fluorescence microscopy, and statistical methods, with scope for plenty more.

Super-planaria

But the true superpower of planaria is tissue regeneration that is even more impressive than a certain Marvel superhero. Individuals in asexual strains reproduce naturally by spontaneous binary fission, with the resulting head portion growing a replacement tail and the tail end growing a replacement head, yielding two complete worms after about a week. This incredible feat is attributable to stem cells (called neoblasts) that comprise as much as 30% of the worm. Since neoblasts are the only mitotic cells in planaria they drive all cell replacement during homeostasis and regeneration. Therefore, planaria are highly efficient stem cell factories. They have basic cell signalling mechanisms in common with higher organism so understanding how to manipulate neoblasts toward specific fates may inform stem cell therapies.

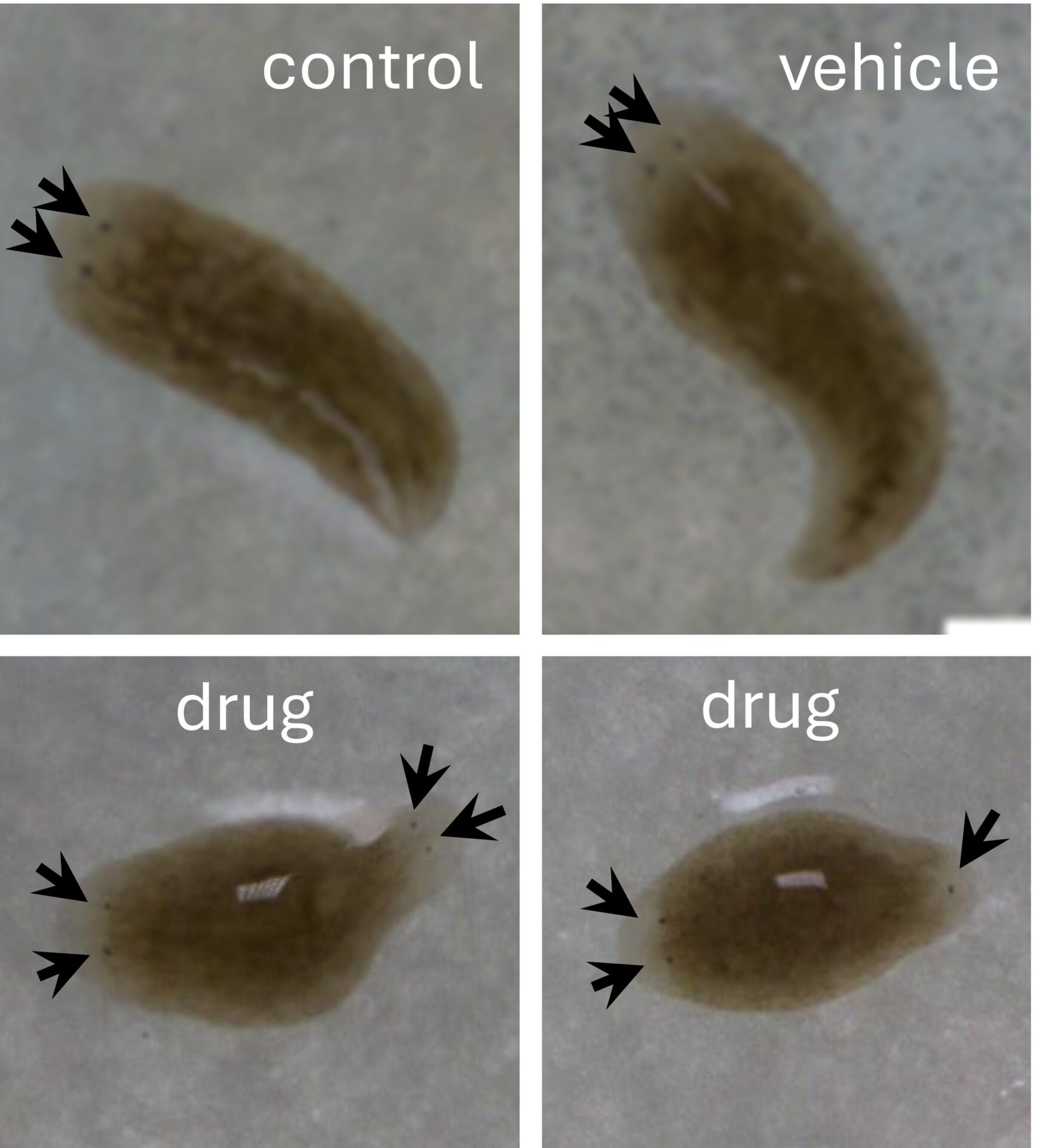

Experimentally, a scalpel mimics fission. Although planaria can be cut into many fragments with each piece generating a new individual, worms are typically cut into three fragments for study. Observations tend to focus on the regenerating middle (trunk) fragment, which faithfully grows a new head and a new tail simultaneously at the appropriate ends. This can reveal whether experimental manipulation has altered neoblast fate (e.g. two-heads or no-head).

An adaptable planaria- based practical

I have run a practical for several years using planaria to test the role of voltage-gated calcium channels in driving head-tail neoblast identity in regenerating trunks based roughly on a published study (Nogi et. al., 2009). The practical, which supports lectures on planaria stem cell biology is done in my laboratory with sets of up to 15 level four undergraduates working in pairs over two 3h sessions spaced a week apart, but it could be done in a teaching laboratory.

Before the first session students received a manual with background reading, protocols, and a video of planaria amputation. Students then calculated how to make the drug stock solution, the necessary dilutions, and vehicle controls. On arrival in the lab their calculations were checked, we discussed experimental design, including appropriate controls, and how many animals were needed for meaningful statistical analysis. Then they prepared the solutions and dilutions, amputated the worms on ice under a dissection microscope, and placed the trunk fragments into appropriate solutions in a dark cupboard to regenerate.

A literature search would indicate that the drug is expected to subvert regeneration of posterior ends of trunk fragments toward ectopic head regeneration (two headed worms), but controls should regenerate normally. After a week students returned to the lab to record regeneration outcome, photographing worms with the dissection microscope, and recording head-tail regeneration and mortality. Data were pooled across all groups and each student wrote a report as a 2000-word research paper.

This lesson is popular because the students find the planaria to be engaging (cute) and they are excited to create two-headed animals. They also gain skills across wet lab work, group work, calculations, data presentation, statistics, and scientific writing.

Low cost, flexible, scalable

A highly attractive aspect of this practical is that it is very inexpensive to run, even for large classes. In addition to a planaria colony and your selected drug, it only requires basic laboratory tubes and dishes (or cheap kitchen storage tubs), pipettes, gloves, filter paper, ice, scalpels, and artificial pond water (or some brands of mineral water). The only potentially costly equipment is a dissection microscope fitted with a colour camera. In a pinch, the amputations and observations can be done using a mounted magnifying glass (available from Amazon) and a modern phone (ideally with a macro camera lens) using laminated graph paper under the dish for scale.

There is no upper limit to how many students can do this practical if they work in groups. In a large class different groups could use drugs with different physiological targets, or different concentrations of the same drug. Using planaria does not require a Home Office license and the colonies are cheap and easy to maintain in a plastic lidded tub in a laboratory cupboard (the worms are photophobic). To grow and multiply happily the colony only needs weekly feeding on liver paste followed by water replacement.

Planaria can be used for practicals across many disciplines, including physiology, pharmacology, neuroscience, toxicology and biological sciences. For example, testing behaviour (e.g., body twisting or photosensitivity) in response to drugs or noxious environmental stimuli only requires planaria, a stimulus and your imagination.

I enjoy sharing my planaria experiences, including at public outreach events where people seem to find them as amazing as I do. If you have been inspired to use planaria- let’s talk.

References

Nogi T, Zhang D, Chan JD, Marchant JS. (2009) A novel biological activity of Praziquantel requiring voltage-operated Ca2+ channel β Subunits: subversion of flatworm regenerative polarity. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 3(6): e464. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0000464